In many respects, the past year in Ukraine has demonstrated how war never really disposes of any old idea. Instead, ideas and organisations are combined in different and sometimes new ways depending on the aims and will of the combatants.

The subject of continuity of war was the theme in my first post in this series. This second part the Year of War series will focus on change.

The war in Ukraine has seen a combination of old and new techniques of war. It has featured ancient elements of war such the destruction or pillaging of cities, the rape and murder of civilians, the employment of state and non-state combatants in physical combat and information warfare, as well as the conduct of psychological operations to erode the will of combatants and civilians alike.

The war in the past year has also featured new uses of modern technology. More importantly, it has driven three key innovations likely to transform how future wars are planned and fought. These are: meshed intelligence systems; autonomous systems; and new ways of generating influence.

Meshed Intelligence

The meshing of civil and military intelligence and information has been a significant change in military affairs in the past year. Military organisations have always relied on communications, and networks, to inform themselves about the strength and locations of their adversaries, supply locations, routes, and information about themselves. The invention of the internet not only improved communications but it has provided access to many heretofore inaccessible or unaffordable sensor technologies for more people than ever before.

Data from open-source technologies has been exploited by both sides in the Ukraine War. These open-source sensors often utilise older versions of contemporary military technology. And while sources such as the NASA FIRMS may provide only rough approximations of events related to military activity, these can be correlated with other open source information to make it militarily useful.

But intelligence activities are about assembling multiple layers of information to build a complete picture or hypothesis of what those layers mean. The ability of open-source sensors, including satellite imagery and scraping data from social media, to detect battlefield activity means that military institutions must be even more careful and clever with their signature management in the 21st century.

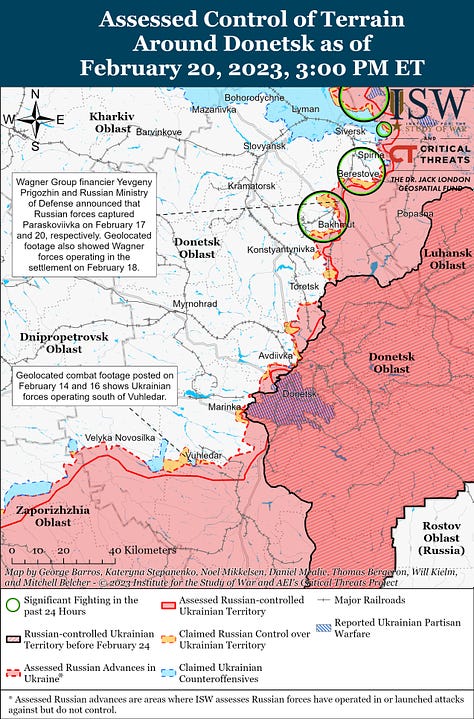

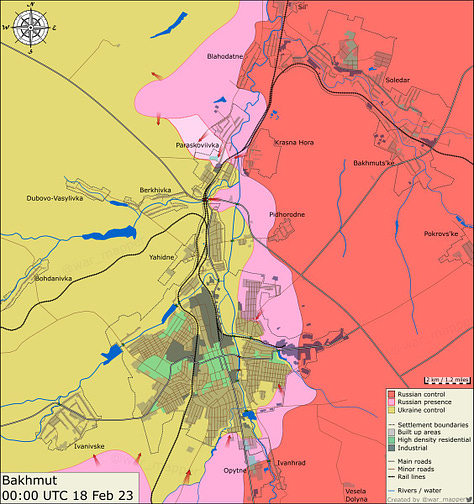

The war between Ukraine and Russia has also seen greater involvement of third party, open-source intelligence analysis capabilities that use data mining, geolocation and other collection methods as their raw materials. Bellingcat and Forensic Architecture are two examples of private or university-based companies involved. Another example of this private intelligence analysis is the Washington DC-based Institute for the Study of War which uses an ‘all open sources’ method to collate and analyse the war, as well as issuing daily campaign updates on its progress.

This approach has evolved to incorporate the independent surveillance of conflict zones and detection of non-declared state-based combatants and weapon systems. The pervasiveness of these actors in the contemporary environment highlights how transparent military operations have become to civilian surveillance, collection and analysis organisations.

Another form of third-party participation in intelligence collection in Ukraine has been online hackers. Independent hackers and hacker teams supported operations on both sides of the conflict. For example, reports early in the war suggested that Ukraine had been able to amass an army of volunteer hackers over 400,000 strong. These hackers have allegedly been employed in attacking Russian sites, combating Russian misinformation and defending against what has been described as “an aggressive, multi-pronged Russian effort to gain a decisive wartime advantage in cyberspace”.

In a recent Foreign Affairs article, Amy Zegart explores what she describes as a revolution in open source intelligence in the war in Ukraine. She describes a new world of meshing civil and military collection, analysis and dissemination of intelligence. Importantly, she concludes that:

Secret agencies are no longer enough. The country faces a dangerous new era that includes great-power competition, renewed war in Europe, ongoing terrorist attacks, and fast-changing cyberattacks. New technologies are driving these threats and determining who will be able to understand and chart the future. To succeed, the U.S. intelligence community must adapt to a more open, technological world.

It is not just the Americans, but also the rest of us who will need to ponder, learn and adapt to this new era in intelligence. Henceforth, military, government and civilian collection, analysis and dissemination of intelligence will need to be more tightly integrated to underpin military success.

Enter the Robots (and Robot Killers)

Military robots have been used since the Second World War. However, their use has expanded massively since the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. A variety of other military applications were discovered during these wars for uncrewed robotic systems, including disposal of improvised explosive devices, aerial delivery of supplies and searching restricted spaces under the ground. Autonomous systems have featured throughout the war in Ukraine, with both sides employing dozens of military and civil systems.

Autonomous systems, and robots in human-robot teams, have a wide variety of future military applications. Human-robot combinations will be useful in training establishments to improve training outcomes and provide the testbed for best practice in developing human-robot tasking relationships. In logistics, robots will have utility in performing tasks that are dirty, dangerous or repetitive (such as contaminated areas; urban, deep sea and subterranean environments; densely protected military site; but also, more mundane applications such as vehicle maintenance and repair, and basic logistics and movement tasks.

Back in 2018, I published a report with the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments on human-machine teaming. A lot has changed since then! There are several current trends in autonomous systems that have emerged from the war in Ukraine.

First, they have proved their utility across a range of lethal and non-lethal missions in Ukraine. We should expect to see further proliferation after this war. They are too cheap, too available and too capable for military and other national security institutions to ignore.

Second, there has also been a widescale use of commercial autonomous systems to supplement the missions undertaken by military grade systems. Both Ukraine and Russia have supplemented their military systems with a range of different commercial UAVS. Many of these have been provided by civilian crowd funding efforts.

Some commercial drones have been used for recon and surveillance. Others have been fitted with small munitions, such as mortar bombs or 40mm grenades, for dropping on the enemy from above. While of some battlefield utility, these are going to be less effective as counter drone technologies proliferate, and military institutions think through the better implications of integrated human-machine teaming.

Third, counter autonomy has been a ‘lagging capability’. Despite early warning in multiple open source and classified resources about the future use of autonomous systems, counter-autonomy has not kept up with deployment of autonomous systems. It is hard to believe but commercial drones dropping grenades and mortar bombs is still widely practiced in Ukraine.

This topic was explored by the US Defense Science Board in 2020. Their (short) report is available here. While a range of electromagnetic and kinetic solutions are now available, these will need to be supplemented with other new systems that bring down the cost of counter autonomy operations for military organisations. Military organisations will have to develop a new generation of counter-autonomy systems that are cheaper to purchase and deploy widely than it is to purchase and deploy the autonomous systems they defend against. They might even be a future ‘cost imposition’ capability against the use of autonomous systems. Regardless, it has been an area where Ukraine and Russia have sought to out-adapt each other in recent months in what some have called a ‘drone war’..

Fourth, while there is an increasing use of autonomous systems, we are yet to see true swarming operations. The massed attacks by Iranian drones in the last few months were not swarming drones. Swarms are groups of drones coordinated by bespoke algorithms. As this article defines them, swarms are “multiple unmanned platforms and/or weapons deployed to accomplish a shared objective, with the platforms and/or weapons autonomously altering their behaviour based on communication with one another.”

Fifth, the use of autonomous systems has been restricted mainly to the air domain. While the Russians have deployed remote controlled mine clearing robots, that is about it for non-air domain autonomous systems in this war. Given the Russian claims of developing several uncrewed combat ground vehicles over the past decade, this probably indicates that these are immature and unreliable. It is doubtful that the Russians have not used them due to ethical concerns.

However, there are more recent reports of both Ukraine and Russia intending to deploy uncrewed ground vehicles for combat and logistic functions. Ukraine is likely to deploy THeMIS uncrewed vehicles, and Russia may use the Marker uncrewed combat vehicle. If these prove their utility, we will see a proliferation of them across many battlefield functions on both sides of the war. Many other nations will be watching with interest.

Finally, the term ‘integration’ is potentially an over exaggeration in the military application of autonomous systems in Ukraine. We are yet to see deep, systemic integration of autonomous systems – across the domains – in the tactics of either side. Autonomous systems are still a ‘low density’ capability in military organisations. However, the ratio of humans to robots will flip in the near future. Our warfighting concepts, and training approaches, will need to evolve to ensure we are able to best able to exploit lethal and non-lethal autonomy across all domains.

Influence Operations in Ukraine – and beyond

War has always been about achieving a complex balance of physical, intellectual and moral forces. Influencing the thinking and actions of enemy commanders, and political leaders, is as old as war. The actions that are undertaken as part of influence activities include disinformation, subterfuge, and – importantly for our purposes here - military deception.

Advanced 21st century technologies have not only enhanced the reach and lethality of military forces. These advances have also provided the technological means to target and influence various populations in a way that has not been possible before. The ability to influence leaders, their advisors, the inhabitants of their nations is more sophisticated, more targeted and more pervasive than ever before. The ability of modern states, corporations, and non-state actors to devise and test strategic messages – targeting different groups with different narratives - through the internet and social media, adjust it and access millions of users almost instantly is unprecedented.

But as the past year of war in Ukraine has demonstrated, the ‘influence playing field’ is not entirely dominated by techno-authoritarian regimes. In the lead up to the 24 February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the intelligence agencies of the United States were able to use sensitive sources and reporting to attempt to pre-empt Russian operations. These releases of previously secret intelligence discredited Russian narratives about the war as well as crowded the information space to degrade the impact of Russian influence campaigns.

The most noteworthy example of effective influence operations has been the Ukrainian Government, and its President in particular. Ukraine has run a model program to influence western governments and gain aid and diplomatic assistance since the beginning of the Russian invasion. This is being studied by many other nations.

Social media is particularly influential. Social media has revolutionised global communication, social interaction, marketing and professional discourse. It has demonstrated a capacity for penetration and influencing perceptions of humans that is historically unprecedented, particularly when compared to other means of communication.

Other wars have been covered by social media. Examples include the Israeli operations in Gaza over the past decade as well as the application of social media by ISIS during their invasion of northern Iraq. The rise of citizen social media war commentators was noted in a 2013 paper titled The New War Correspondents. But there has been a massive expansion in this approach during the last year. Thousands of online commentators – some well credentialed and experienced, some not experienced at all – have gained a high level of influence among populations in Russia, Ukraine and in many western nations. Analysts have developed sophisticated mapping products to track progress in the war and have shared countless numbers of images and videos which all exert some level of influence on those who view them.

This has been a role traditionally reserved for a small number of specialist journalists, otherwise known as war correspondents. The older generation of war correspondents have adapted quickly, combining their traditional reporting approaches with the exploitation (and verification) of social media geolocation and other data to report on the war. There are risks however. An over reliance on social media information (which is more difficult to verify and very open to lies and deception) is a risk for government and military leaders. As Chris Warren has written, "We’re still working out just what ‘truth is the first casualty’ means in the social media age.”

The war in Ukraine has seen a Cambrian explosion in new age war correspondents and analysts. Support from non-government influence actors – including the global #NAFO movement and artists producing images such as the popular Saint Javelin – has also provided important reinforcement to messaging from Ukraine, NATO and the US about the war. The contemporary pervasiveness of social media, new era correspondents and analysts, as well as human and AI influencers, in nearly every environment humans fight means military commanders and planners must incorporate them into their planning processes.

The Character of War Continues to Evolve

Carl von Clausewitz wrote in On War that “war’s character, its conduct, constantly evolves under the influence of technology, moral forces (law or ethics), culture, and military culture, which also change across time and place.” We have watched over the past year as the interaction of Russian and Ukrainian forces on the battlefield and in the information domain have battled for advantage.

This competition has spawned several innovations in the conduct of war. While this article only explored three of these changes in the character of war, there are sure to be many more that will become evident as this war progresses. And while we may not see every innovation by the belligerents, their actions, reactions and evolutions are resulting in multiple asymmetries between Ukraine and Russia. That will be the subject of the third and final article in this series.

This article is the second of a three part series being published in the lead up to the commemoration of one year since Russia commenced its latest invasion of Ukraine. The final article will explore asymmetries that have developed between Ukraine and Russia stemming from their learning and adaptation since 24 February 2022.

Excellent piece - thanks for posting!

Bravo, Mick.