China is Learning About Western Decision Making from the Ukraine War

A Special Assessment on Ukraine and how Western decision-making is informing the strategic calculus of Chairman Xi and the CCP

What lessons is China learning from Russia’s war on Ukraine?” is a question that preoccupies many senior policymakers in Washington and other Western capitals. The hope is that Russia’s experience in Ukraine will deter Beijing from invading Taiwan. But Beijing may be drawing different conclusions in the third year of this gruelling war than it did in the first. And the lessons China’s leaders are learning may be the opposite of those the White House wants them to learn.

Xi Jinping Has Learned a Lot From the War in Ukraine, Alexander Gabuev

Wars are full of uncertainty.

Whether it is the uncertainty of what the enemy is doing on the other side of a hill, through to uncertainty about the motivations of political leaders in their decision-making, the ‘fog and friction of war’ is every bit of relevant in considering war in the 21st century as when Carl von Clausewitz wrote about this concept in the early 1800s.

However, sometimes there are things in war that we can be certain about. I would propose that one certainty of the Russo-Ukraine war is that China is watching it closely. In particular, it is learning to improve its strategic decision models (within the bounds of the CCP system) by watching U.S. and NATO decision-making and responses to the Ukraine war. Chinese aggression in the South China Sea and around Taiwan is also prompting Western debates which inform China’s strategic calculus.

I have explored the topic of Chinese learning from the Ukraine War in several previous articles. My first examination of China’s potential observations from the war in Ukraine was published back in April 2022. This was designed as short, initial exploration of what China might learn from the conflict. A year later, in February 2023, I undertook another exploration of how China might be using the war in Ukraine to wargame its own future operations. Finally, in September last year I published a piece here that proposed multiple areas where the Chinese leadership might be learning from the war in Ukraine.

Nearly a year later, I wanted to provide an assessment on one particular aspect of China’s (potential) learning from the war in Ukraine that has political and strategic impact. As such, in this article I will examine how China might be learning from how the West (the U.S. and NATO in particular) have made strategic decisions during the war, up to the latest debate on long range strike, and how this will inform and influence Chinese strategic decision-making.

China Learns from Foreign Wars

The PLA are careful and meticulous students of modern warfare, particularly the U.S. way of war. But despite recent organizational reform efforts, the PLA remains essentially a political entity with a war-fighting mission. It is a party army, not a national army. And its approach to learning and leadership is heavily influenced by its own organization, as well as traditional Chinese culture and education.

What the Chinese Army Is Learning From Russia’s Ukraine War, Evan A. Feigenbaum and Charles Hooper

China, and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), have previously demonstrated both the willingness and ability for learning and change. In 2023, Toshi Yoshihara examined China’s study of the lessons of the Pacific War. As he writes in his report, published by the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Studies,:

Chinese analysts, including those affiliated with the PLA, have subjected the maritime conflict and its campaigns to scrutiny. The historical accounts render clear and sound judgments about the sources of operational success that in turn reveal much about the PLA’s views of strategy and war… Chinese findings from these retrospectives offer tantalizing hints of the PLA’s deeply held beliefs, assumptions, and proclivities about future warfare, such as the penchant for striking first and attacking the enemy’s vulnerabilities.

Yoshihara finds in his study of Chinese learning from the Pacific War that Chinese scholars see jointness and amphibious operations as key features of the Second World War. Another topic of interest is the role of shore-based airpower and its influence on the conduct of operations. Other themes in the Chinese writings are the crucial role of intelligence and reconnaissance, and the attrition of forces on both sides, including Japan’s lack of industrial depth and personnel to sustain and recover from its combat losses. The report contains a good bibliography of Chinese sources which I highly recommend.

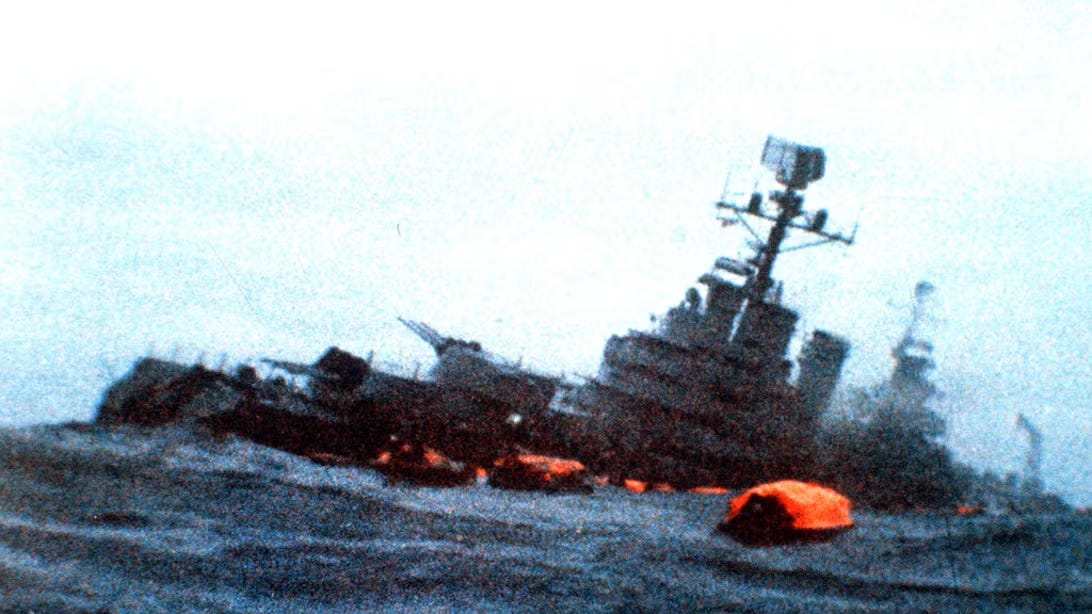

The Falklands War, the first modern conventional war in the post-Vietnam era, was a case study in the strategies, successes, and failures of the Argentine military as it attempted to deny British forces access to the waters surrounding the islands. The lessons have probably contributed to China’s anti-access/ area-denial (A2/AD) strategies, with its lessons in sea denial and maritime attack. Few wars more analogous to a Taiwan Strait operation than the Falklands War. The war showed the lethality of new era missile systems as well as the challenges of long-distance force projection, which would be a challenge for those coming to Taiwan’s assistance.

As Lyle Goldstein has written on this topic: “this author conducted an academic survey of Chinese writings regarding the Falklands War that was published in 2008. That study revealed that Chinese strategists admired London’s objective use of intelligence and its “flexible, joint, and efficient command arrangements.” The airpower discussion notes that the Argentines lacked effective anti-ship doctrine and the related weaponry…one Chinese assessment of the Falklands War concluded that the sinking of the Belgrano cruiser by a Royal Navy nuclear submarine proved to be “the most decisive military operation of the Falklands War.”

James Holmes has also written an interesting piece on Chinese learning from the Falklands War. You can read his article here.

The 1991 Gulf War shocked the Chinese military into a multi-decade recapitalization of its military, and indigenous research and development programs, which has included advanced ships, aircraft, missiles, cyber and space warfare and ground combat vehicles. It has also resulted in reforms to strategic and operational command and control, including better joint integration. Chinese lessons from the 1991 Gulf War – as well as the wars spawned by 9/11 – have included a reformation in their operational doctrine and has resulted in concepts such as ‘intelligentization’ and ‘systems destruction warfare.’

Recently, several experts from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) conducted a study of Chinese writings on the war in Ukraine. Their findings, not surprisingly, indicate that China is studying the war very closely. Every aspect of warfighting, from the national level to tactical operations, is being reviewed by different Chinese scholars and military theorists. You can read the commentaries on Chinese learning from the CSIS experts, as well as translated Chinese articles, here.

China has an evolved capability to study and learn from other people’s wars. Partially this is due to necessity; China has not been involved in large-scale war since its disastrous invasion of Vietnam in 1979. The poor performance of the PLA in that war saw Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping use it to overcome resistance from PLA leadership for the modernisation of China’s military. But China has since then used its studies of other peoples’ war to inform change in the PLA. The most recent conventional war in Ukraine, like the other wars discussed above, provides an array of lessons. And perhaps the most important lesson is how Western nations make decisions about war.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Futura Doctrina to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.