In my posts over the past few weeks, I have been exploring the hypothesis that Ukraine has developed its own, unique way of warfare. My explorations of this theoretical construct extend beyond the examination of the battles and campaigns that have been conducted since the Russian large scale invasion in February 2022.

Building and sustaining a warfighting capability is a national effort. It demands the construction and constant adaptation of a military strategy, which is aligned with the overall national (political) objectives of a conflict. Since 2022, although there is a deeper historical foundation as well, the Ukrainians have evolved their own distinct approach to war.

I have been exploring multiple elements of this hypothesis of a Ukrainian Way of War, and my recent visit to Ukraine provided the opportunity to speak with many of the senior military and civilian officials who oversee the strategic components of Ukraine’s warfighting potential. One key subject of my discussions was the human dimension of raising, training, sustaining and adapting a military institution at war.

This human dimension of war, and the need to dominate the mind of an adversary while hardening the minds of our own people, has been a consistent theme in Ukraine. Both sides have mobilised massive armies which have clashed in large scale battles since February 2022. Violence and influence are two sides of the same coin in these battles. And as we witnessed during the huge artillery battles in eastern Ukraine last year, and in other campaigns since, the mind boggling firepower employed causes tremendous psychological as well as physical harm to combatants and civilians.

Moral and Psychological Preparation in Ukraine

To prepare their soldiers for the psychological challenges of combat, the Ukrainian military has evolved a sophisticated, yet constantly evolving approach. During my recent visit to Ukraine, I had the opportunity to meet with the man who leads the efforts to develop the mental resilience of individuals and teams for the Ukrainian military.

Major General Vladyslav Klochkov is a combat experienced, former brigade commander in the Ukrainian ground forces, who leads Ukrainian armed forces General Directorate of Moral and Psychological Support. As Klochkov described to me, “I was appointed by General Zaluzhny to respond to change and oversee the mental readiness of all our people.”

I recently wrote a short piece for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation on this subject. You can read it here. This article is an expanded version that provides more detail about our discussion and wide array of functions that are overseen by General Klochkav.

Learning has been a key part of his role. The Ukrainians have learned much since February 2022 about mental resilience and supporting their people. While the Ukrainian Armed Forces studied lessons about psychological support learned by western armies in Iraq and Afghanistan, the intensity of this war meant an evolved model was required. NATO doctrine for personnel support is applied in the Ukrainian Armed Forces, which includes the NATO JP-1 publication and several STANAGs. However, this has been adapted and supplemented due to the nature and scale of the current threats to Ukrainian military personnel.

Ukrainian soldiers are exposed to sustained close combat and the kinds of artillery barrages, over long periods of time, that no western army has experienced since the Second World War. Adding to combat stressors, soldiers have to deal with Russian minefields and the ubiquitous presence of drones on the battlefield. Mines are threats that several generations of western soldiers have not had to prepare for. Drones, particularly of the lethal variety, are a new threat. Rarely have contemporary soldiers had to look up for threats.

Finally, there is also the stress of possible capture. While exact figures have not been released, both sides have captured thousands of their opponents soldiers. The treatment of these Prisoners of War is governed by the Third Geneva Convention of August 1949 on the Treatment of Prisoners of War. As Article 13-14 and 16 of this convention state:

Prisoners of war must not be subjected to torture or medical experimentation and must be protected against acts of violence, insults and public curiosity.

The Russians routinely and systemic ignore this and many other articles of the Geneva Conventions. According to Ukraine’s Coordinating Headquarters for the Treatment of POWs, 78% of returned Ukrainian POWs have been tortured by Russia. As such, mental resilience for the Ukrainians must - unfortunately - prepare them for not only the shock of possible capture, but the high likelihood of torture while a PoW of Russias.

Another challenge for the Ukrainians is that the scale of the conflict means they have a limited ability to rotate units away from the front line. Major General Klochkov has a research centre that has produced studies on how long soldiers should be left in combat situations before being rested. In the broad, he described to me their findings that humans can adapt to combat conditions for about 15 days and endure frontline conditions for about 60 days before their performance begins to significantly degrade.

However, despite this, battlefield requirements mean that soldiers are routinely exposed to much longer periods of combat than the research recommends. Brigades and units, by military necessity, must remain in contact with the enemy - or on the front line - for longer than 60 days. Consequently, mental resilience and psychological hardening is a critical element of training for Ukrainian soldiers.

The shape of the Ukrainian Armed Forces has also changed significantly since February 2022. When the Russians began their large scale invasion, the Ukrainian military had around 200 thousand personnel. Since then, it has mobilised its population and now deploys a million person military. This creates a range of issues. As Klochkov noted during our conversation, “Regular army and mobilised army people are very different.”

With over three quarters of a million new members having been inducted in the past 18 months, the Ukrainian military must now mentally prepare people from an even more diverse array of backgrounds than in peace time. This is not entirely negative - this has resulted in many new ideas and skills flowing into the military. But nonetheless, it imposes a mammoth task on the training system and those who must ensure that military personnel are psychologically prepared for the extreme rigours of modern combat.

The Ukrainians use a mix of old and new techniques to mentally prepare their soldiers. Live ammunition is used in training from very early on to acclimatise soldiers to the sounds of bullets passing close by. Trainees are exposed to explosions, fire and heat to build their resilience to artillery barrages and other explosions. They are also exposed to an environment with drones and an array of other battlefield threats. Animal entrails and blood is used in activities to condition recruits to the sights, touch and smells they will almost certainly encounter in a high casualty battles.

Cultural activities form another important pillar of this mental preparation for combat. The Ukrainians have found that learning about their culture builds team cohesion. Crucially, it provides a clear purpose for their soldiers. It ensures they know what they are defending against in the existential threat of Russia. But, these cultural activities are also an important part of post-combat decompression.

Another important aspect of moral and psychological support is what Klochkov calls “national combat traditions restoration.” This includes a range of activities that are vital for espirit de corps such as individual and unit awards and the assignment of honorary names to military units.

While important, there is also minimal time for all this in the training continuum of the Ukrainian Armed Forces. Ukrainian soldiers receive a month of recruit training followed by about a month of specialist training such as infantry, engineering, artillery and other skills. Every moment counts and the intensive psychological preparation is designed, as General Klochkov notes, to “ensure our soldiers can control their stress, panic and fear.”

But pre-combat training and mental hardening only goes so far. Klochkov describes the Control Groups which have been formed to support deployed personnel. These are designed to provide a prompt response to “changes in the moral-psychological state of military personnel” during operations.

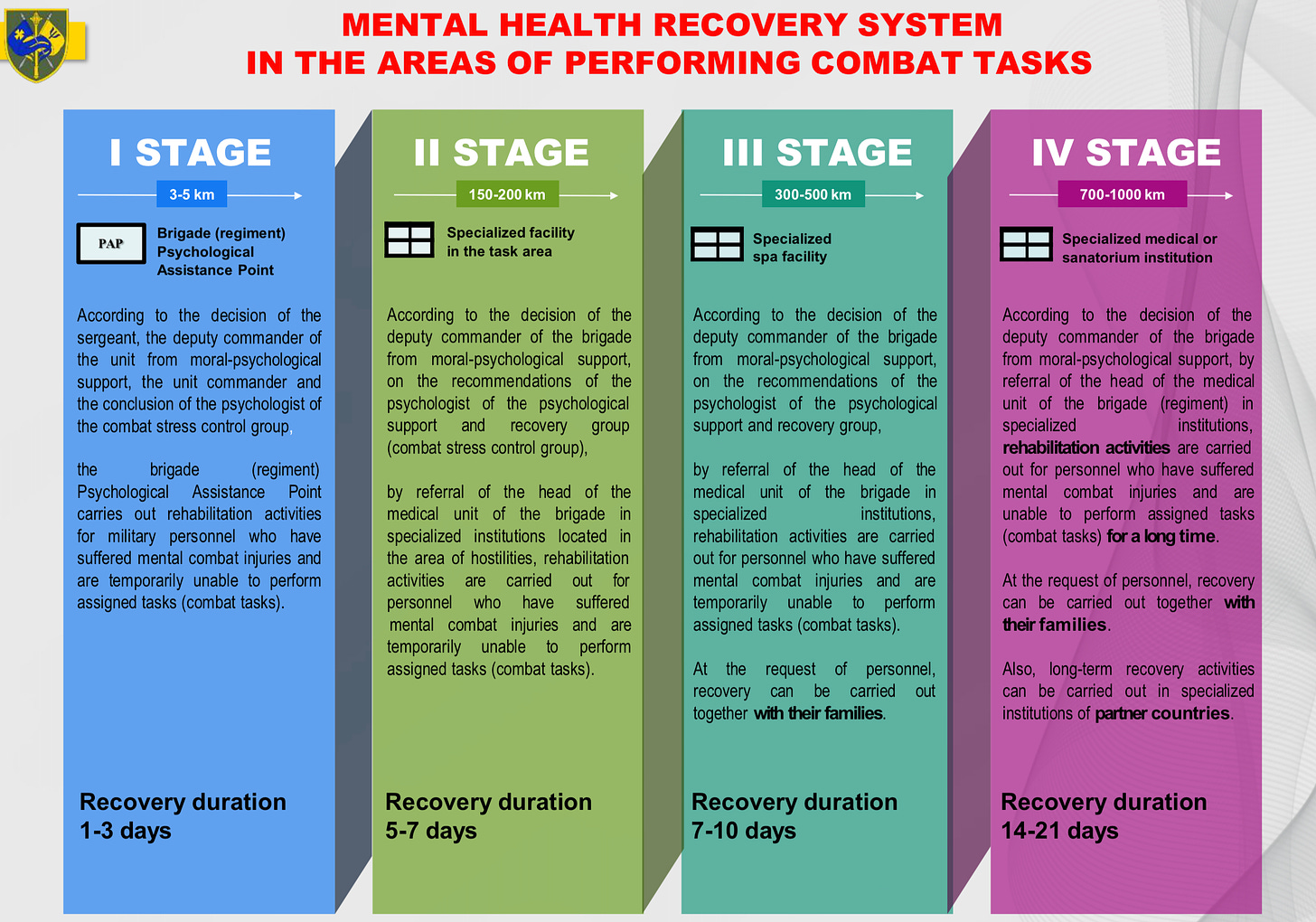

Three stages of psychological support is provided to military personnel:

Stage 1. This is a combination of self-assistance, support from fellow soldiers and commanders as well as the initial assessment and evacuation from the battlefield if needed.

Stage 2. This is the first assistance by a psychologist officer, and diagnosis. This can also include evacuation to a “psychological assistance point.”

Stage 3. This includes support provided at a Brigade psychological assistance point, medical and psychological supervision and further evacuation to military hospitals.

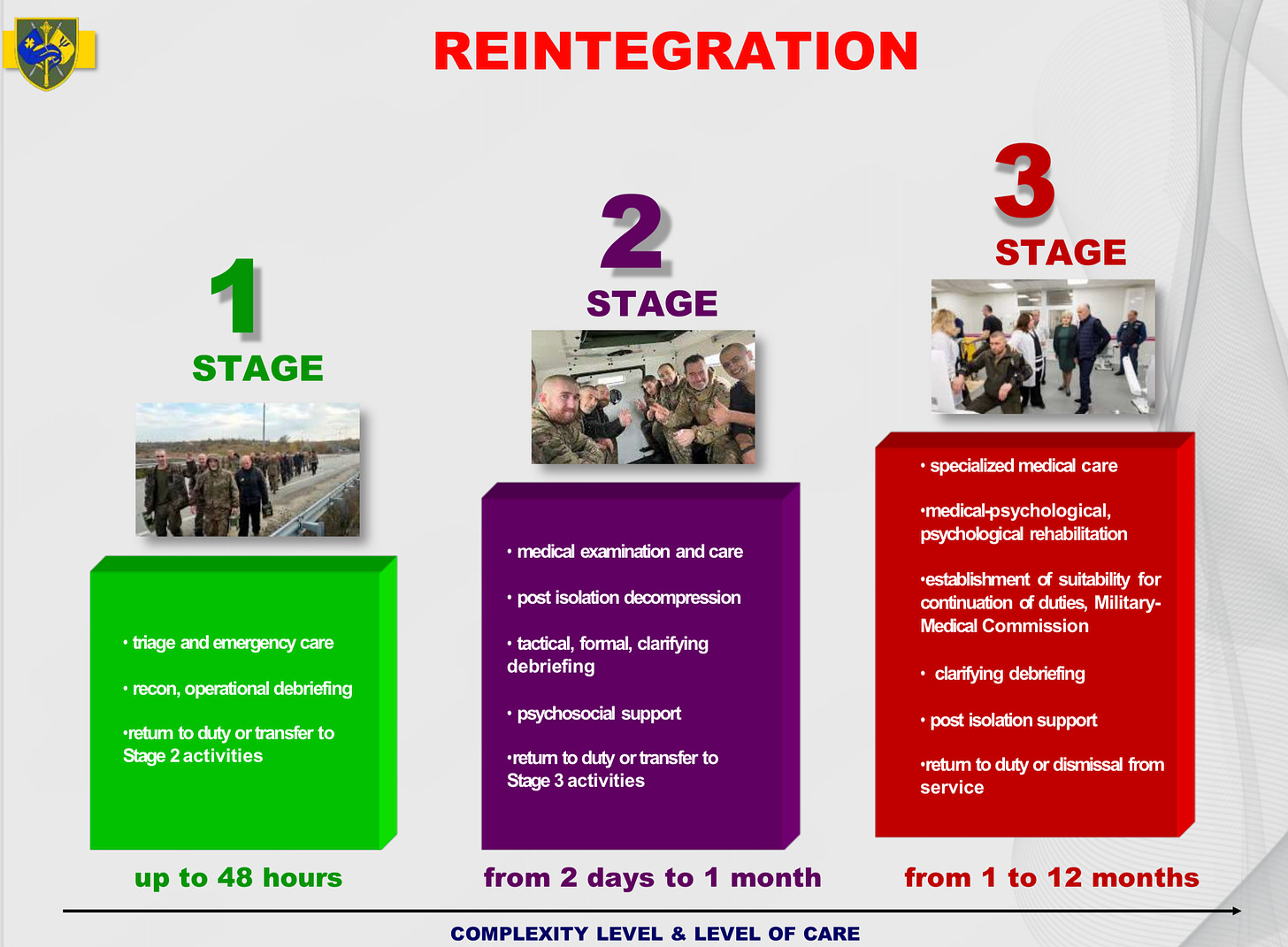

The Ukrainian military has also implemented the processes for psychological recovery and reintegration, which are shown below.

The magnitude of the challenge has resulted in an organisation led by Klochkov that undertakes research, conducts support through smart devices and mobile teams to military personnel on the front lines, and oversees the resilience - and resilience refreshing - for all Ukrainian military personnel. It also has an important role in the reintegration of military personnel back into society and support to families.

Human Resilience in the Ukrainian Way of War

Back to my hypothesis about a unique Ukrainian Way of War.

It is hard to imagine such a construct of warfighting without a strong foundation of human capacity, endurance and resilience. Preparing people for war not only hardens them mentally, and builds cohesive teams, it also ensures they are educated in appropriate combat behaviours. These behaviours, which encompass looking after one’s own health and that of their team mates, also encompasses how one treats enemy combatants.

Killing is something that is necessary for soldiers. It is a skill and an art that all armies prepare their people for. But it is not wanton killing or the undisciplined killing of non-combatants. Adherence to international laws - and the values of one’s society - is an important contextual aspect of how and when soldiers kill.

Throughout this war, the Ukrainians have demonstrated significant restraint in how they treat enemy combatants. They appear to have treated prisoners of war humanely and avoided - to the extent possible - civilian casualties in their strategic strikes on Russia. Indeed, fighting a ‘just war’ is a key element of Ukrainian strategy.

But to do this takes the appropriate conditioning of soldiers. They must kill when necessary in combat but no more. This is both an individual imperative to preserve their mental health as well as a strategic attribute for Ukraine.

Consequently, I propose that the kind of moral and psychological support that is provided through training, combat and post combat recovery periods, as well as family support is an important aspect of the larger Ukrainian Way or War.

Learning from Ukraine

While these initiatives are specific to Ukraine, there are insights to be gained about modern conflict, and preparations of soldiers, sailors, aviators and marines for war, that other military institutions need to study.

During the two decades that the western military institutions conducted operations in places such as East Timor, Iraq and Afghanistan, there was a reinvigoration of learning about the psychological impacts of military operations on our people. New preparation and post-operations screening and support mechanisms were established. But as traumatic as these conflicts were for our people, they were very different in nature to the constant, searing violence of the firepower-intensive conflict in Ukraine.

Rarely did we have to ‘look to the skies’ for threats in the wars spawned by 9/11. U.S. air power, supplemented by its allies, essentially owned the skies at every altitude. If a drone did fly overheard, it was almost always friendly. This did, however, begin to change during battles against ISIS in places such as Mosul in Iraq. But, these operations did not result in any measurable change in our doctrine.

We face a very different environment on the contemporary battlefield. This is something that requires a capability solution and the hardening of our people’s minds against the threat.

While recent strategic documents from the U.S., Japan, Australia and elsewhere might describe a pathway for the physical form of for their nations’ future defences, an even more crucial commitment must be made to the resilience, preparation, and post-combat support to military personnel (and their families). The conditions of modern warfare, with Ukraine as an example, will be far more violent and demanding than anything seen by the western military institutions in the past several decades.

Klochkov is the kind of battle-experienced leader needed to lead strategic military personnel agencies. He is enthusiastic about his responsibilities, has seen the impact of combat, and is keen to share what he has learned with other military institutions.The kinds of initiatives being implemented by Major General Klochkov and his organisation are worthy of closer study by the leadership of the western military organisations. As he noted towards the end of our discussion:

We may sometimes miscalculate in our operational plans, but we always care about our people. How would western systems currently in use work if they had to expand their forces massively like Ukraine has?

That is a very good question indeed.

Brilliant work, Mick! It is so often forgotten the psychological, morale, and team building preparation and healing that needs to be undertaken for any organization to be effective, let alone the military. In this way the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

Unfortunately in the US, we see the after effects of not carrying out these functions well, not that the US military does out try. We also now see this false bravado from those in the right who decry these ideas as being “woke” and “soft.” Yet those with that attitude never have had to serve or faced such privations. How does one get through to such people who have reached levels of decision making?