In the second half of 2003, I returned to Australia after two years studying at the Marine Corps University in Quantico. It had been a fascinating two years. My family and I arrived in Quantico in July 2001. Little did we know that just two months hence, events would unfold that would fundamentally change domestic security in the United States, and in the global security environment more broadly.

On return to Australia in July 2003, the United States and my home country had conducted military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. The occupation of Iraq was unfolding and the security situation in Afghanistan was beginning to unravel, which would see the redeployment of Western forces there in the years ahead. In Australia’s immediate region, we were involved in military operations in East Timor and the Solomon Islands. It was a demanding time operationally.

At the same time, the Australian Defence Force was engaged in an early 21st century effort to transform itself to respond to new technologies and new-era threats. In the year before I returned to Australia, two fundamental publications had been released that aimed to chart an evolved course for how the Australian Defence Force for the next two decades thought about warfighting, other military operations, and the myriad of supporting activities to build this capacity.

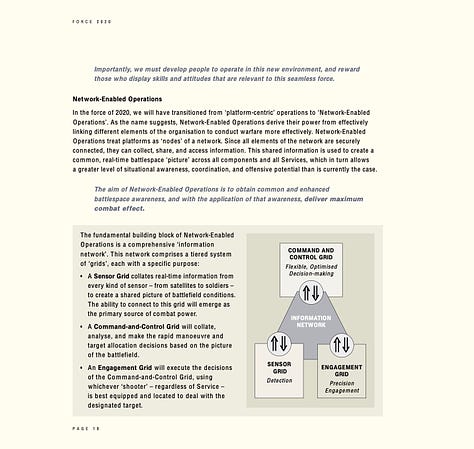

The first of these was Force 2020. Published in 2002, it provided an updated scan of the security environment, and how new technologies were changing the kinds of threats that would need to be addressed by 21st century military institutions. Importantly, it endorsed key strategic ideas about how the Australian Defence Force should be ‘raised, trained and sustained.’ This included concepts such as a ‘seamless’ joint force and networked operations.

The second important document was the Future Warfighting Concept. Endorsed in 2003 just before I arrived home in Australia, this was designed as a subordinate element of the Force 2020, focussed primarily on the Australian Defence Force’s warfighting capacity. The central idea was that of Multi-Dimensional Manoeuvre, which the document described thus:

Multidimensional Manoeuvre is based on using an indirect approach to defeating the adversary’s will to oppose us. This approach seeks to negate the adversary’s strategy through the intelligent and creative application of effects against the adversary’s critical vulnerabilities. The approach also considers the adversary as intelligent and adaptive; consequently, we need to take measures to protect our own strategy.

So, I was arriving home in July 2003 to work in an institution that was intellectually preparing itself for changed security circumstances in the years ahead, as well as conducting the development and experimentation with the warfighting ideas that would guide procurement of new equipment and weapons as well as shape training and education of our people.

My new job on return to Australia was to lead the development of future joint warfighting concepts at Russell Offices in Canberra. For a just promoted Lieutenant Colonel, it was an exciting assignment, which required much study of current trends in warfare as well as collaboration with procurement, policy and experimentation staffs in both joint and single service headquarters.

My first task was the development of the Australian Defence Force’s first Network Centric Warfare roadmap. This was a fascinating undertaking, demanding cooperation with all elements of our military and civilian elements in the Department of Defence. But eventually we produced a classified plan which was endorsed in November of that year.

Ever since, I have been involved in futures and strategic planning for both our Army and Australian Defence Force strategic headquarters. Along the way, I have also had the opportunity to command various units, attend multinational experimentation events, network extensively and publish reports and many articles on issues related to strategic development and adaptation of military forces. I have also been fortunate to play roles in major institutional reform programs such as the Adaptive Army changes in 2008, and leading institutional reform for both Army and Joint training and education.

In some respects, the culmination of this experience, education, thinking and practice over two decades was the publication of my book, War Transformed, in February 2022. And while I retired from active service in the very same month, my interest in developing effective future military institutions – and contributing the institutional programs to achieve this – has remained undiminished.

The Future of War

For that reason, I have added a new section to my Futura Doctrina substack page called The Future of War.

I retain a passion for exploring the conflict in Ukraine and the strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific and will continue publishing on these topics here. However my studies of the phenomenon of war and the various pathways it might take can provide insights into building effective tactical and strategic forces in the future, as well as providing a useful foundation for the exploration of contemporary wars.

My continued exploration of the future of war is necessarily broad. To that end, I will utilise a framework that contains four key lines of inquiry. These are:

1. The Phenomenon of War and Learning from the Past.

2. Trends in Military Affairs.

3. Learning from the Present.

4. Learning from Narratives

Lines of Inquiry

The Phenomenon of War & Learning from the Past. It is difficult to understand what we might observe in wars such as that in Ukraine without some fundamental knowledge about war. One important framework for understanding war as a phenomenon is that provided by Carl von Clausewitz in On War. There, he writes about war’s changing character as well as its enduring nature. This is an important construct because most wars are an aggregation of all the wars that have preceded it, with some new technology, ideas or context on top. I will refer back to this notion of changing character and enduring nature of war in my exploration of future warfare.

But there are other theorists and scholars of war that bear study as well. There are the well-known ones such as Sun Tzu, Thucydides, Jomini, Machiavelli and others. There are those who specialised in certain domains of war such as Mahan, Corbet, Douhet, Mitchell, Simpkins and Trenchard. And then there are historians and scholars such as Azar Gat, John Boyd, John Keegan, Margaret MacMillan, Williamson Murray, Amy Fox, JFC Fuller, Michael Howard, Hew Strachan, Liddell-Hart and many others.

My strong belief is that it is almost impossible to discuss contemporary or future war without a very good grounding in the development of military theory, as well as a broad and deep understanding of military history. As such, military theory and history will be a constant touch stone in my exploration of future warfare.

Trends in Military Affairs. Armed with military theory and history as a base, we are able to better recognise changes in military affairs and the conduct of human competition and conflict. And if we can discern changes, trends might then become apparent which can shape evolution – or even transformation – in military institutions. Such trends are not only about new technologies, although these are important. Generally, trends in military affairs feature different mixes of technologies, ideas, organisations and people.

To that end, I offer seven import trends in military affairs that will guide my exploration of future warfare. These seven, which I examined in War Transformed, allow us to understand how the character of war is continuing to evolve. They are:

The battle of signatures, where military organisations must minimize their tactical to strategic signatures, use recorded signatures to deceive, and be able to detect and exploit adversary signatures—across all the domains in which humans compete and fight.

New forms of mass, where military organizations must build forces with the right balance of expensive platforms and cheaper, smaller autonomous systems that will be more adaptable to different missions and be more widely available.

More integrated thinking and action, where unlike the counterinsurgencies of the past two decades, future military institutions must be able to operate in all domains concurrently and integrate into broader national strategies.

Human-machine integration, where robotic systems, big data, high-performance computing, and algorithms will be absorbed into military organizations in larger numbers to augment human physical and cognitive capabilities, to generate greater mass, more lethal deterrent capabilities, more rapid decision-making, and more effective integration.

The evolving fight for influence, where disruptive twenty-first-century technologies have not only enhanced the lethality of military forces at greater distances, but they also now provide the technological means to target and influence various populations in a way that has not been possible before.

Greater sovereign resilience, where nations must mobilize people for large military and national challenges, while also developing secure sources of supply within national and alliance frameworks to ensure that supply chains cannot be a source of coercion by strategic competitors or potential adversaries.

A new appreciation of time. This is an underappreciated resource. With the profusion of algorithmic approaches to war, hypersonics and autonomous systems, war is speeding up and actions will be measured in micro-seconds. At the same time, we are engaged in a long-term competition, and must develop improved political and societal capacity and patience for implementing strategies that will play out over decades. Democracies specialise in 24 hour cycles, and election cycles. But they are weak in dealing with microseconds and decades. This has to change.

Learning from the Present. Learning from current events – be they politics, wars, or strategic competitions – helps to provide evidence for new trends or to discount them. At the same time, the study of contemporary wars provides insights into new trends and how the character of war is evolving.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Ukrainian defence of their nation, is offering a vast trove of observations, and eventually analysed lessons, about the character and conduct of modern war. Like all wars, it features many elements which are not new. These include many of the technologies (tanks, missiles, aircraft) and ideas (combined arms tactics, trench systems, the need for good leadership) which have featured in many past wars. At the same time, we are seeing new technologies (autonomous systems) and ideas (meshed civil-military sensor nets, digitised C2) that is likely to change the structure and thinking of many military institutions around the world.

The challenge in this is deciding which lessons are relevant only to the war being observed, and which lessons might have wider applicability. Notwithstanding this, the contemporary pace of change in technology and geopolitical affairs means that military institutions will need to take some risk in developing their own capabilities because the security environment may not afford them the years they might normally utilise to make procurement decisions based on observing current conflicts.

Consequently, observations on contemporary conflicts and strategic competitions will feature as part of my exploration of future war.

Learning from Narratives. Finally, part of my examination of the shape of future war will include narratives and military fiction. Narratives have played a role in thinking about future war since the dawn of the Second Industrial Revolution at the end of the 19th century. And it all started with a British Army officer named George Chesney.

In the late 1860s, Chesney had become concerned over the poor state of the British Army. He authored a fictional story that highlighted shortfalls in the defence of Britain. His story described an invasion of Britain by a ‘German-speaking’ nation that he called The Enemy. Published in 1871 in the wake of the Prussian victory over France in the Franco-Prussian War, the book was a sensation. It quickly sold over 80,00 copies and sparked a national debate on the Britain’s defences.

This was the start of the modern future war genre, which ever since has featured both fiction and non-fiction accounts of war in the future which now includes Ghost Fleet and my own White Sun War.

Fiction can assist institutions to deal with massive change in technology and society, which are features of past (and the ongoing) industrial revolutions. Readying, and producing, military fiction is also a brilliant way to unleash the creativity in military personnel who often exist in hierarchical systems which stifle innovation. And finally, fiction which utilises good research can be employed inform public debate and test new ideas.

Lawrence Freedman wrote an excellent book on the application of narratives recently called The Future of War: A History. And recently there has been the adoption of military fiction by different military organisations around the world to broaden the education and innovative spirit among military personnel. During my time as Commander at the Australian Defence College, I ran (for four years straight) an elective for students that saw them develop papers for the Australian Chief of Defence Force.

As such, military fiction and narratives will also feature in my exploration of future war here.

A New Adventure

I am really excited by this new chapter in Futura Doctrina. I won’t be neglecting my coverage of Ukraine or Taiwan. But my examination of the many aspects of future warfare will hopefully only enhance my capacity to analyse these conflicts and write about the lessons they offer us all.

I look forward to sharing this journey with you.

The books in the “Future of War” genre that were the biggest influence on me were the “Third World War - August 1985” series by General Sir John Hackett.

Of note (and if memory serves) many of the “future systems” used in Hackett’s fictional war between NATO and the USSR are now being employed in Ukraine.

My copies were destroyed in a house fire 30 years ago, but you’ve inspired me to buy replacements and read them again.

Thank you for your work and dedication. Lots to think about here!

Respectfully, I would ask if there is a typo in the list of lines of inquiry. Should #3 be learning from the present? Current text below.

My continued exploration of the future of war is necessarily broad. To that end, I will utilise a framework that contains four key lines of inquiry. These are:

1. The Phenomenon of War and Learning from the Past.

2. Trends in Military Affairs.

3. Learning from the Past.

4. Learning from Narratives