It has been nearly three weeks since the initial ground combat phase of the Ukrainian 2023 offensives commenced. Of course, even this was just part of a larger preparatory phase which began in late 2022 and has taken months to assemble equipment and munitions, train soldiers, collect intelligence, shape Western perceptions and attack Russian operational and strategic enablers.

In an interview with the BBC this week, President Zelensky described how progress in the Ukrainian 2023 offensives has been "slower than desired”. He then described how "Some people believe this is a Hollywood movie and expect results now. It's not." This was a useful statement from the Ukrainian president for a couple of reasons.

First, his statement is an acknowledgement that military campaigns are very difficult to plan and assemble and are infinitely more complex to execute over time and space. The Ukrainians are fighting through a deep defensive regime constructed by the Russians (more on that later), which the Russian forces have had months to construct. Further, the Ukrainians don’t have air superiority due to the glacial decision making of Western nations on provision of fighter jets.

Second, any slowness of these offensives is partially due to the slow commitment and arrival of foreign military aid at the end of 2022. Despite an appropriate desire by Ukraine to win the war more quickly, it is unlikely that this offensive could have begun sooner due to the individual and collective training requirements for western equipment.

The demands of halting the 2023 Russian offensive year will have complicated the timing of this offensive. Begun shortly after Gerasimov assumed command of the overall Russian special military operation in Ukraine, the Ukrainians still needed to defend large swathes of their land against Russian thrusts on several axes. They did so successfully, but it consumed time and resources.

Back to the present.

The Ukrainians are in the initial phases of their offensive. But what does that mean from the Russian and the Ukrainian perspectives?

Russian Scheme of Defence and Doctrine

Some have called the Russian defensive scheme across eastern and southern Ukraine the Surovikin Line. Given much of the initial design would have been undertaken for the defence of Russian occupied territory during his command tenure, this makes sense. It also allows Gerasimov to use Surovikin as a scapegoat if the Russian defences fail.

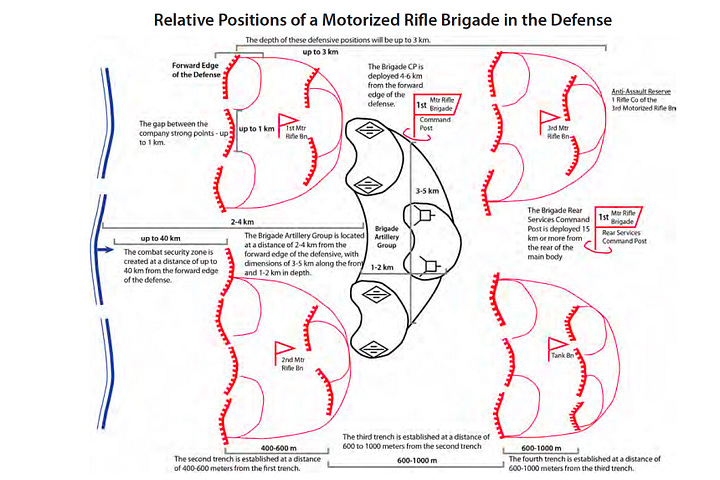

It is worth examining Soviet and Russian military doctrine to understand how these defences are laid out. Every army has some form of doctrine that provides guidance on how to design, construct and execute a defensive scheme of maneuver. I have attached below the doctrinal templates for Soviet and Russian armies. They are very similar. Most Western armies also have doctrine like this, and if you looked at NATO defensive schemes during the Cold War, you would see many of the same features.

Defensive schemes have a security zone, which extends for tens of kilometres in depth. This will have a low density of defending troops, which have missions to collect information on advancing troops, impose attrition on them, and force delay upon them. During this time, longer range fires will probably also be used against high value targets of an advancing enemy, including engineer breaching assets, headquarters and artillery.

Well behind the security zone will be the main defensive position or positions. These will generally consist of at least two echelons, depending on how likely it is that an enemy will use this axis of advance. Deployed behind these main defensive positions are the various artillery units, which will have been pre-registered on key anticipated enemy routes and assembly areas.

Also, behind the main defensive positions will be the different reserve forces that senior commanders have formed. These will possess varying degrees of mobility depending on their allocated missions. Generally, you would expect these to be mainly mechanised or armoured forces. They will be charged with counter attacking where enemy forces have seized ground or undertaking counter-penetration missions to cut off and destroy enemy forces that have penetrated the main defensive positions.

Compare these doctrinal templates of Soviet and Russian defences, with the live map available at the Institute for the Study of War. There is a clear main defensive position, with a security zone forward and a secondary defensive zone to the rear. Every army in the world would find it tough to fight through this.

The next level of design and layout of a defensive scheme of maneuver is how to get best from the ranges and effects of different direct and indirect weapon systems. This will depend on the ground, how much time there is to develop the defences, whether this is a static or mobile defence as well as the obstacles being used. One example of how all the different weapons of a unit are integrated is shown below.

These doctrinal prescriptions of defensive layouts have emerged over decades. They are the product of the hard learned lessons of historical combat. In that way, they provide useful standardised approaches for developing a defence, and understanding the resource requirements of them.

Finally, these doctrinal approaches by the Soviets, Russians and other armies permit less experienced troops to be used in defensive schemes of maneuver. Historically, most troops involved in such operations had minimal training; they were not the hyper-professionalised and exquisitely trained soldiers of contemporary Western military institutions. As such, having these doctrinal layouts helps the Russians given their large numbers of newly mobilised troops.

Finally, it should be noted that these defences are not evenly constructed across the entire front. In some areas, terrain prevents such approaches. But, more generally, they are most dense where the Russians will have done an appreciation of Ukraine’s most likely objectives for their offensive. The interesting thing in the coming weeks will be if the Russian appreciation of Ukraine’s most likely and most dangerous (to Russia) courses of action match the actual Ukrainian campaign plan.

It is a very complex undertaking, and is certainly much more than digging a few trenches, laying a few mines and deploying units into their bunkers and other positions. But here’s the thing. While the Russians need to defend a very long front line, the Ukrainians only need to create a single breakthrough. How they do that is the subject of the next section.

The Ukrainian Design – Operations Across a Broad Front

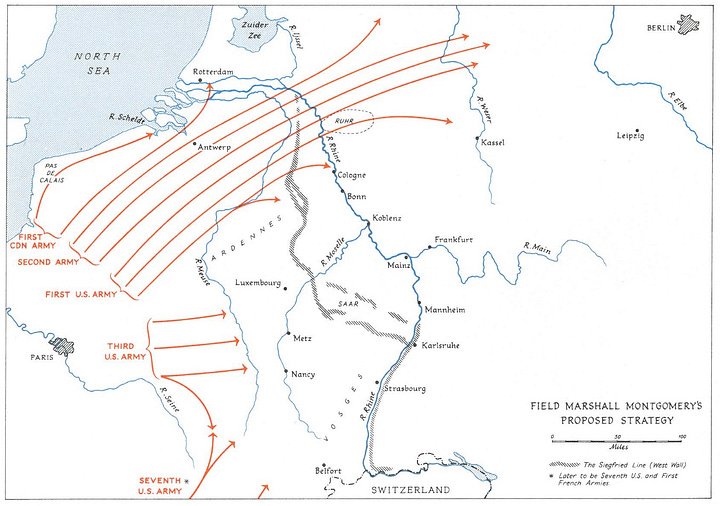

One of the great debates of the later stages of the allied advance through France in World War Two was whether to conduct the advance on a broad front or a narrow front. The key advocate for the narrow front design was Field Marshal Montgomery. He proposed that the majority of allied combat divisions (British, Canadian and US) be allocated to a thrust into northern Germany.

On 4 September 1944, he wrote to Eisenhower stating that:

I consider we have now reached a stage where one really powerful and full-blooded thrust towards Berlin is likely to get there and thus end the German war.

Eisenhower responded that:

While agreeing with your conception of a powerful and full-blooded thrust towards Berlin, I do not agree that it should be initiated at this moment to the exclusion of all other maneuvers...

Later that month, Eisenhower also reinforced this with the view that a large-scale drive into the "enemy's heart" was unthinkable without the opening of the port of Antwerp. He would not change to a narrow front because it would lengthen logistic lines of support more quickly than they could be developed.

The failure of Operation Market Garden largely put paid to the plan, as did the continuing failure to secure Antwerp. Additionally, if the majority of combat forces were concentrated in a narrow front in the northern part of the European theatre, Eisenhower would have had limited capacity to adapt and exploit opportunities if they presented elsewhere.

The Ukrainian design for their offensive campaign in 2023 appears to have embraced a broad front approach. There are a few reasons why this is the most logical strategy for them to adopt.

First, it generates uncertainly in the minds of Russian commanders. They don’t really know where the main weight of effort for the Ukrainian ground offensive will fall. It permits better operational security for the Ukrainians. It also enables a wide variety of deception operations, as well as tactical feints and demonstrations to provoke the Russians to deploy reserve forces before they need to. The longer the Ukrainians can keep the Russians in this sense of unease and uncertainty, the better.

Second, because the Ukrainians are operating on interior lines, it makes it simpler to conduct logistic support to combat forces. These interior lines, which shortens routes between different areas of the front line also makes it easier for the Ukrainians to redeploy larger formations from one part of the country to another.

Third, operating across a broad front allows for more capacity to respond to opportunities when they arise. If a force is overly concentrated in one area, not only is it more vulnerable to attack on the modern battlefield, it is less able to adapt and exploit enemy mistakes across the entire front line. A broad front strategy, while it does disperse the force more, provides for a wider array of responses where opportunity arises.

Finally, there is a political imperative to defend as much of Ukraine as possible. Concentrating a large proportion of Ukraine’s ground forces in one area (notwithstanding the excellent contributions of regionally focussed Territorial Defence Forces) might expose Ukraine to Russian tactical and operational thrusts to take more territory.

Russian response - Gerasimov Takes Option 2

In my recent article reviewing the options available to General Gerasimov to respond to Ukraine’s 2023 offensive, I described one of his options as follows:

Option 2: Hang Tough (plus). Gerasimov’s next option is a variation on Option 1, but with limited offensive jabs at Ukrainian weak spots if they open up. This is a more complex option because he would need to assemble the combat and support forces for an offensive operation from his already weakened force.

It appears that the Russians, rather than sitting back passively across the entire front line, have chosen this option. Over the past couple of weeks, the Russians have conducted attacks on the Donetsk, Avdiivka, Bakhmut, and Siverskyi Donets axes. While the Russians have made minimal headway in these attacks, they are demonstrating that their offensive capacity is not entirely exhausted.

These Russian attacks also might mean that Gerasimov is concerned about the Ukrainians developing momentum on the southern front and seizing enough territory to place Crimea at risk. In many respects that is the nightmare scenario for Gerasimov. As such, he will be desperate to draw more Ukrainian forces to the eastern for a war of attrition and deny them the ability to participate in the Ukrainian southern campaign.

How long the Russians can sustain these attacks in the east is questionable. They have just completed a tactically and operationally unsuccessful 2023 offensive, and lost masses of troops and equipment while doing so. Given the Ukrainian preparations for their current offensives, it is likely that the Russian attacks in the east will culminate long before the Ukrainian offensive of 2023 does.

The State of the Campaign

One of the things that good military institutions do during combat operations is conduct periodic, high-level campaign assessments. These measure progress in offensive activities against the objectives laid down the in the original campaign design. Very rarely is there a perfect correlation between the two, even this early in a campaign. As soon as an offensive commences, the enemy acts in ways that are both predictable and unpredictable, requiring adjustment to the original design. The Ukrainians are very likely to have been undertaking campaign assessments since the beginning of their current offensives.

What kind of insights might we draw from what we know so far about this Ukrainian offensive, noting we have a very imperfect understanding of the battlespace, force dispositions and the ultimate capacity of troops on both sides?

First, the air defence environment over the battlefield is a challenge. The exhausting strategic air defence battle fought over Ukrainian cities and critical infrastructure has probably drawn away more air defence assets than those leading the campaign would prefer. This was a political judgement, and the right one, but it still complicates life for tactical and operational commanders. While the Ukrainians have already begun to adapt and have shot down more Russian battlefield helicopters in the past few days, more tactical air defence assets will probably be required to protect ground combat, support units and headquarters.

Second, combat and combined arms obstacle breaches are very difficult. We knew that going into these offensives and there was much discussion about it during the past six months. But sometimes, it is only when these tactical activities begin that we can understand the true nature and strength of an enemy defensive schemes of maneuver. Satellite photos, contrary to popular opinion, do not see everything. Camouflage and concealment can hinder observation, and no satellite image can assess morale, will or command intentions. As such, this phase of the Ukrainian operation will be focussed on fighting for information and assessing Russian strengths while also seeking to confirm the Russians overall plan.

Third, the strategic information fight continues to be vital. The Russians have the easier time with this because they don’t have to tell the truth, and they only need to convince people that Ukraine is not winning. Their messaging since the beginning of the Ukrainian offensive has focussed on projecting Ukrainian failure to western and other audiences. Ukraine, on the other hand, has to preserve operational security while rolling out a synchronised campaign design. At the same time, it needs to make available sufficient information about its successes to push back on the handwringers who want a ceasefire and peace talks. Such an outcome now would only favour Russia. Balancing these imperatives will remain a challenge for Ukraine. But, it must win this influence battle to sustain Western support in the second half of 2023 and into 2024. Remember: a lack of news is not the same as a lack of progress.

Fourth, offensives consume huge quantities of fuel and ammunition. Ukrainian tactical and operational logistics, and their strategic supply lines, will be critical to the success of their offensives. Preserving them against Russian attacks will be vital. Sustaining Western production of munitions and the shipment of munitions into Ukraine in sufficient quantities and in timely fashion will also be a determinant of success and failure in the Ukrainian offensives.

Finally, the offensive is yet another demonstration of war as a contest of wills. Clausewitz knew it and wrote about it, and it is every bit as true today as it was 200 years ago. Tactical success for the Ukrainians will be helped by many physical elements but ultimately it is determination, commitment and leadership that brings together all of the tools of war to get soldiers through the defensive regimes constructed by the Russians. But strategic and political will is every bit as important. While the Ukrainians fight and die to liberate their territory and preserve their nation, those of us not at risk must hold our nerve, provide support and sustain our collective will to prevent Russian barbarity from succeeding in Ukraine (or beyond).

An excellent piece.

Mick, you allusion to Market Garden is quite apt and a great lesson for the Ukrainians. Clearly Ukraine are not making a concerted push in one area and searching for any weakness they can find. But that is what the Russians want. Ukraine will not oblige them. Now if we can get the journalists and others to just have patience...