A Peace Plan for Ukraine?

While there is no plan at present, we can anticipate what some components of a future plan might be.

In the past few days, speculation about a potential ‘Ukraine solution’ from the incoming Trump administration has accelerated. There have been other plans supposedly developed in the past, including a May 2024 proposal written by retired U.S. Army Lieutenant General Keith Kellogg. Under that plan, the U.S. would continue to arm Ukraine to deter Russia from attacking during or after a deal is reached, but under the condition that Kyiv agrees to enter into peace talks with Russia.

Now, a report in The Telegraph describes an evolved plan that includes a buffer zone, freezing the conflict, Russia retaining currently held territory, ‘pumping Ukraine full of US weapons’ to deter Russia and deferring Ukraine’s NATO membership for years.

It is timely to examine some of the components of these plans, and the issues they might contain. We can only explore potential components because the reality is that there is not yet an endorsed Trump plan for Ukraine. And, unfortunately, nor is there a U.S. strategy for Ukraine that has been produced by the Biden administration in the past three years.

Possible Ukraine Plan Components

The potential components of any future Trump administration plan may include some or all of those examined in the following paragraphs.

Freezing the conflict. If the conflict were to be frozen along current lines, this would leave Russia occupying almost 20% of Ukrainian sovereign territory. A central objective for Ukraine in this war has been to take back all of its territory occupied by Russia and return to the 1991 borders. While not impossible, this looks very difficult at the moment given Russian advantages in manpower and its very extensive defensive works which it has been developing since the end of 2022.

Additionally, the Russians currently have strategic and operational momentum in Ukraine. As the diagram above shows, the Russians have accelerated their capture of Ukrainian territory over the course of their nearly year-long eastern offensive. This is despite massive, and increasing, casualties. The Russians will feel they will be negotiating from a position of strength if there are peace negotiations and will be reticent to give any concessions.

Ukraine may hope that retaining some parts of Kursk will give them some negotiating power. However, the Ukrainian Kursk offensive, designed to change the trajectory of the war, hold Russian territory at risk and force a military and political response from Putin, has not achieved these objectives. And, with a rumoured 50-thousand-person Russian-North Korean force assembling for a major offensive there, Ukraine may not hold much – or any – of Kursk by the time negotiations begins.

Finally, freezing the conflict means many Ukrainians will be left in occupied Russia. There is more than sufficient evidence of the systemic looting, rape, murder, torture, arbitrary shooting of POWs, and kidnapping of children in Russian occupied Ukraine. This has been documented by Ukrainian government agencies, academics and western researchers such as Jade McGlynn. It would make any freezing of the conflict at currently held territory a strategic failure and a moral failure by Western political leaders.

A Buffer Zone. The most recent leak of information includes the creation of a 1200-kilometre (it’s Europe, I will use metric) buffer zone. In essence, this will be similar to the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) that separates north and south Korea. The difference here is that the Korean DMZ is 250 kilometres long; the Ukrainian one would be nearly five times its length. This is an extraordinarily long piece of terrain to ensure separation of the two parties, and if it is to be seeded with mines and other devices to prevent crossing, could take years to put in place. And, like the Korean DMZ, a Ukrainian DMZ could be required for many decades into the future.

And how wide might the buffer zone be? This will almost certainly be a contentious issue between Ukraine and Russia. Both will want it to be on the territory owned by the other side. Most likely it will extend an equal distance to whatever the front line is on an agreed date. But how far in each direction? A 2018 Comprehensive Military Agreement signed by North and South Korea an example of how a buffer zone might be established, but also how it can fail. North Korea ripped up this deal in 2023.

The other feature of the Korean DMZ is that U.S. forces maintain a presence on the Korean peninsula as part of the overall strategy of maintaining the armistice between the two Koreas. There is no such proposal for Ukraine on the table currently. Indeed, any presence of U.S. troops has been dismissed by those inside the Trump camp (as it was by Biden nearly three years ago). Therefore, it will require the presence of other military forces to guarantee the peace and enforce the conditions of any negotiated deal related to the buffer zone. And that’s where things will get really interesting.

A Peace Keeping Force. In the report in The Telegraph, Trump insiders have been reported to have stated that troops to enforce the buffer zone should come from the UK and Europe. As one news source notes:

"We are not sending American men and women to uphold peace in Ukraine. And we are not paying for it. Get the Poles, Germans, British and French to do it," a member of Trump's team said.

There are a couple of issues with this. First, both Ukraine and Russia would need to agree about which nations would provide troops for a peace keeping force. After all, the UK and Europe have been providing weapons to Ukraine for the past few years that have been used against the Russians. It is unlikely Russia will agree to a Euro-centric force. Instead, it will probably insist on a mix of European, Central Asian and African nations, and that it be under United Nations authority. This will be a tricky negotiation.

Another issue with the peace keeping force will be the willingness of nations to provide forces. Countries around the world have watched this war and learned about the extraordinary lethality of the modern battlefield. If most nations were unwilling to send their troops to the relatively less dangerous southern Afghanistan in the 2010s, why would we think nations would be willing to commit forces to what will probably be the most dangerous 1200 kilometre stretch of ground on earth?

Verification Measures. If there is a ceasefire or armistice, verification measures will be required. While this will be largely the role of the peacekeeping force, other aspects of any agreement that will need to be verified might include the following:

Concentrations of forces of a certain size within a set distance of the buffer zone.

Movement of aircraft within a given distance of the buffer zone.

Any contravention of the conditions agreed to for the ceasefire or armistice.

At this point, it is worth defining some of the outcomes of any negotiations between Ukraine, Russia and any third parties. The first possible outcome is a truce, which is an informal halt to fighting, normally local and short term. This is probably the least desirable outcome but one that might be useful while negotiations take place. A second outcome is a ceasefire, which is a negotiated agreement to cease hostilities. These normally only pause a war, not end it. Finally, we could see an armistice, which is a formal agreement to cease military operations in a war. It ends a war, but still requires that a peace treaty be negotiated and agreed.

All of these will need some level of verification.

Supplying More Weapons to Ukraine. This is one of the more interesting elements that have emerged from leaks about a Trump administration peace deal for Ukraine. The key question is this: do the U.S. and Europe actually have the capacity to step up the shipment of weapons to Ukraine in the short to medium term. So far, they have provided large amounts of their existing inventories but at an insufficient pace for Ukraine to win the war. There has been some expansion of defence industrial capacity over the past three years, but it is unlikely to be sufficient to provide for an increased, faster delivery of western weapons to Ukraine.

Two other issues will complicate this. First, the U.S. has a range of warfighting plans which stipulate the holdings of various equipment and munitions. The U.S. military, in seeking to rebuild its inventories and build larger warfighting stocks to deter future Russian and Chinese military aggression, will have a say in the type, quantities and pace of weapon deliveries.

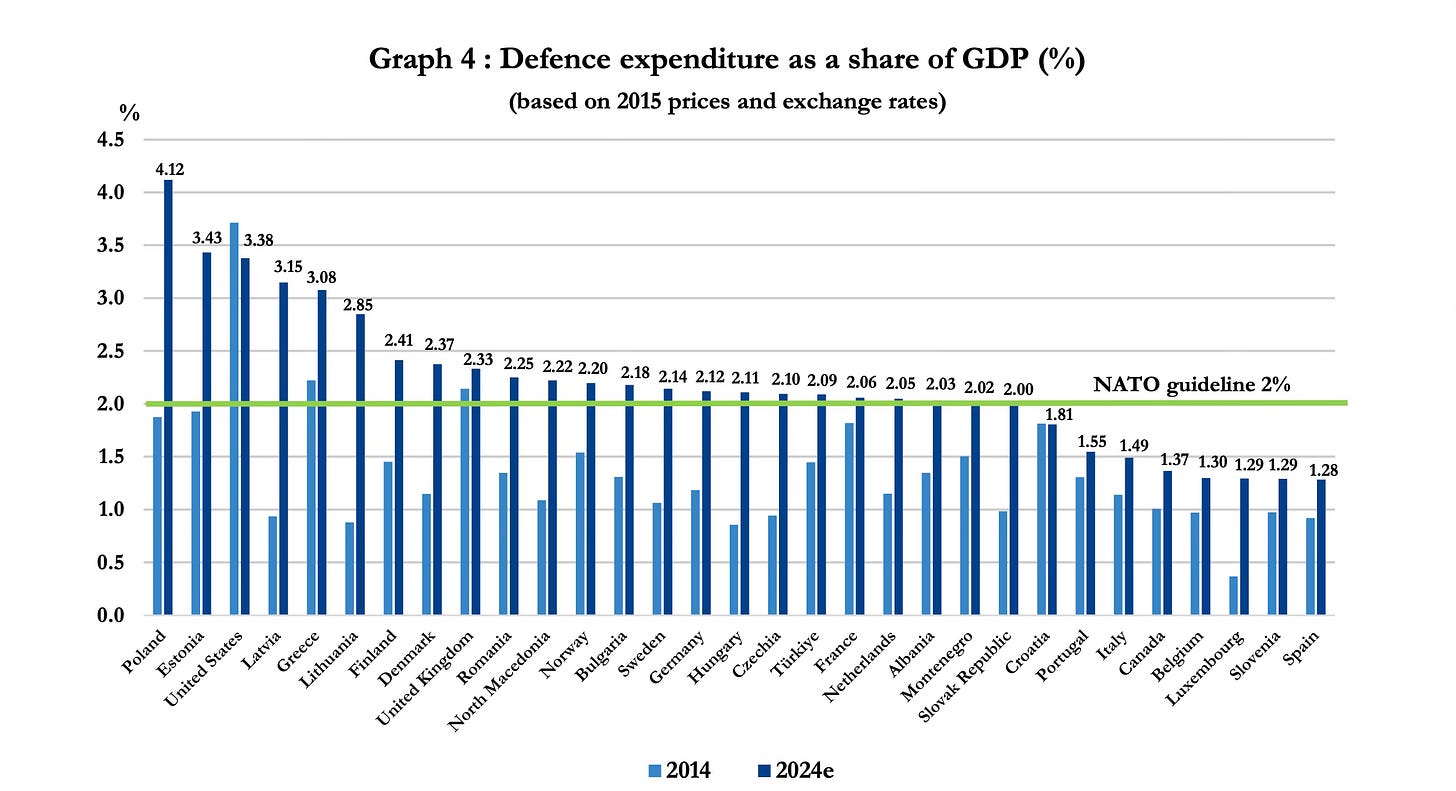

The second complicating factor will be that demand for U.S. weapons from other countries may spike during a Trump administration. Even a cursory review of NATO’s own figures shows that many nations are either just barely, or not, meeting the NATO baseline of 2% of GDP expenditure on defence. If a Trump administration decides that higher baseline is required for cooperation with U.S. forces, this could see large orders for European and western weapons. Where Ukraine will sit in the priority list in this scenario remains to be seen.

No NATO or deferred NATO for Ukraine. This will be a significant blow for Ukraine, given membership of NATO, as well as other security guarantees, has been the centrepiece of Zelenskyy’s peace proposals. The 2023 Vilnius Summit Communique stated that:

We fully support Ukraine’s right to choose its own security arrangements. Ukraine’s future is in NATO. We reaffirm the commitment we made at the 2008 Summit in Bucharest that Ukraine will become a member of NATO.

Deferring membership for decades will be seen as the alliance going back on the commitments it has made to Ukraine that it would have a pathway to NATO. They may still be able to spin that it is a longer pathway than anticipated, but it will be seen for what it is. The NATO alliance has reneged on a promise, and that will breed distrust inside and outside the alliance.

It will be a capitulation to Russian demands, and this will be a massive win for Putin. This will justify in the minds of Putin, and authoritarians like him, that the Russian aggression against Ukraine has worked because keeping Ukraine out of NATO was a core demand of Putin before the war. And if other authoritarians like Putin believe that military aggression against their neighbours can bear fruit, why wouldn’t they pursue similar approaches?

This deferment of NATO will also provide Putin the time to reconstitute and potentially undertake future operations against Ukraine to secure even more of its territory or depose its democratically elected government. Russia has demonstrated the ability to reconstitute its forces much more quickly than was believed possible after their defeat in the Battle of Kyiv. It is very possible that within five years of any negotiated outcome in this war, Russia could be invading Ukraine again. It is what it did to Chechnya.

Other elements of an agreement. There will be other aspects of peace negotiations that I have not explored here. Some of them will be drawn from the current Ukrainian peace proposal and the ten elements of his peace formula described at the 2022 G20 meeting. Elements such as financial aid to Ukraine, treatment of war criminals, sanctions against Russia (and those supporting Russia) are among some of the more likely features, but there will probably be others.

Conclusion

What the Trump administration’s peace plan looks like remains to be seen. But it comes at a time when Ukraine is under increasing pressure, and Western nations have failed to produce and implement a strategy that would help Ukraine defeat the Russian invasion.

The West’s strategy for Ukraine has been failing for some time. A series of decisions by the Biden administration including slow delivery of weapons, avoiding ‘escalatory weapons’ for Ukraine, denials on long range strike weapon use and refusal to place any NATO boots on the ground early in the war has resulted in Russia believing the West lacks the will to fully support a Ukrainian victory, and that the U.S. president is more afraid of a Russian failure than a Ukrainian failure.

Russian president Putin, having observed the U.S. and NATO decision-making over the past three years clearly believes he now has the measure of his western counterparts. He will approach any negotiations with confidence and will be able to portray Russia’s achievements in this war, despite their great cost, as a Russian victory.

That we find ourselves at this point, when the combined wealth of NATO’s five biggest members (U.S. Germany, UK, France and Canada) is twenty times that of Russia, and their military outstrips Russia in technology, size and capability, is a searing indictment about the strategic thinking, execution and will in what is currently known as ‘the west’.

The West’s strategy for Ukraine is no longer failing. It has clearly failed.

It did not have to be that way. But a generation of western political leaders that were conditioned into slovenly strategic thinking by the long post-Cold War peace and the discretionary, slow-paced wars of the past two decades have been unable to sufficiently adjust their mindsets to deal with the ruthlessness of Putin and his supporters.

There is an old Chinese saying: strangle the chicken and frighten the monkey. It is a saying that a PLA General used with a friend of mine one time. In essence, if you wish to shape the behaviour of a big competitor, attack and destroy a small ally of the competitor.

Unfortunately, the U.S. and NATO ‘strategy’ for Ukraine over the past three years, as well as their strategic impatience and inclination to enter into negotiations with a Russia that has the strategic initiative, means that the West instead has ‘fed the chicken and encouraged the monkey’.

We will regret this. And so, eventually, will our citizens.

Putin loves an adversary’s weakness. Time to admit Ukraine to NATO.

Here’s a counter-proposal: RU surrenders unconditionally, borders are restored to pre-2014, a 20 km buffer zone is created inside RU.