We must all understand very clearly - as clearly as possible - that the Russian forces on our southern and eastern lands are investing everything they can to stop our warriors. And every thousand meters of advance, every success of each of our combat brigades deserves gratitude.

While the Russian occupying forces in Ukraine have assumed the defensive over the past couple of months, that does not mean that they have been on the defensive at every level and in every part of Ukraine. General Gerasimov, who we assume retains overall command of the Russian special military operation in Ukraine, is implementing a defensive strategy. But concurrently he is conducting offensive activities at the tactical and operation levels.

Gerasimov’s Initial Strategic Options

Before we explore Gerasimov’s defensive strategy, let’s review the range of options that were open to him once Ukraine began its 2023 offensives. In a June 2023 article, I explored three broad courses of action that were available to Gerasimov. His strategic options were quite narrow because Putin sees advantage in drawing out the war. As such, holding territory seized from Ukraine had to be the central element in any Gerasimov strategy.

The three broad courses of action open to Gerasimov I identified in June were as follows:

Option 1: Hang Tough. Gerasimov’s first option was to hang tough for the time being and observe the development of the initial phase of the Ukrainian offensive. As such, Gerasimov probably wanted to wait for as long as possible as see where the Ukrainian main effort would be focussed. Gerasimov, possibly mindful of the Kherson-Kharkiv one-two punch last year, will have been watching for operations that are feints and for other Ukrainian deception. Clearly, his preferred option was to retain all Ukrainian territory currently occupied, absorb the Ukrainian offensives, and demonstrate minimal Ukrainian success. In doing so, Gerasimov would probably have hoped to retain sufficient combat power to undertake some type of Russian offensive operations later this year once the Ukrainian offensives culminate.

Option 2: Hang Tough (plus). Gerasimov’s next option was a variation on Option 1, but with limited offensive jabs at Ukrainian weak spots. This is a more complex option because he would need to assemble the combat and support forces for an offensive operation from his already weakened force. This would probably show up quickly in the Ukrainian intelligence collection plan and be targeted. While it might be an option, the Russians have not demonstrated a flair for making major gains with their offensive operations this year.

Option 3: Reorient the Defence. Perhaps the most politically difficult – but militarily effective – would have been a reorientation of the Russian defence around Crimea and the Donbas. This would mean that the Russians would be giving up much (but not all) of the territory they illegally seized since February 2022. This would see them focus their defence on three areas – Luhansk, Donetsk and Crimea. It would have shortened the front line significantly and allowed the constitution of significant mobile reserves for the Russians. However, this would see the ‘land bridge’ to Crimea erased and would be politically impossible for Putin. This may be a useful fallback position if things go badly for the Russians in the coming months but is unlikely to be favourably considered as an option in the current environment.

Gerasimov’s Reaction: Option 2 is Executed

It has become apparent that Gerasimov has decided on Option 2. His main effort is clearly holding onto ground in southern Ukraine, from Donetsk all the way west into Kherson. This is a part of Ukraine that is vital to its economic future, and Russian occupation of this territory denies Ukraine access to important mining and agricultural lands. It also provides an important buffer to reduce the Ukrainian ability to conduct long-range strikes against Crimea or to advance to a position where they may be able to launch a future military operation against Russian-occupied Crimea.

Gerasimov has several supporting efforts.

One is the ongoing series of drone and missile strikes against Ukrainian civilian targets. Recently, this has included strikes against Odesa.

Another supporting effort is the defensive efforts in eastern Ukraine around Bakhmut. Ukrainian forces in the east have made gains around Bakhmut which is placing them in an increasingly favourable tactical position. The main focus of this activity is not the recapture of Bakhmut but to attrit the more elite Russian forces which are now engaged there after the departure of the Wagner Group in June.

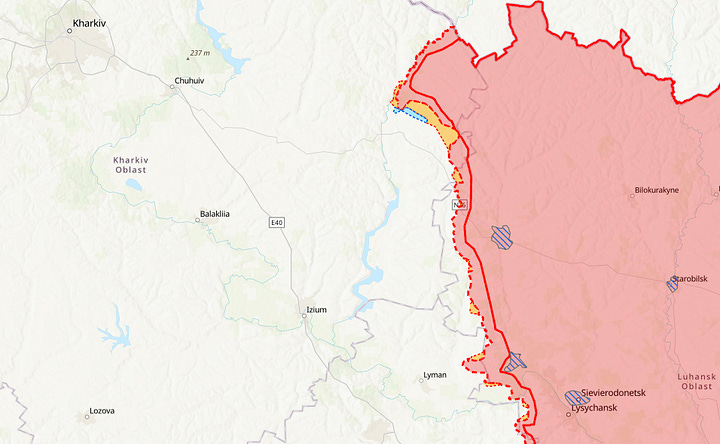

While retaining an overall defensive posture, Gerasimov has also launched a series of attacks (calling it an offensive is too grand) in north-eastern Ukraine. Russian forces have undertaken offensive operations along the Svatove-Kreminna axis, but as the two maps below from 4 June and 23 July show, Russian progress on this axis has been limited.

That said, it does indicate that Russian forces retain some offensive capability. Gerasimov does not intend being entirely passive in his overall defensive strategy to hold occupied territory in Ukraine.

Gerasimov has also launched attacks in Donetsk, with the Ukrainian General Staff reporting that Russian assaults have been repelled over the past month near Avdiivka, Nevelske, Krasnohorivka, Marinka, and Novomykhailivka.

The attacks in Luhansk and Donestk are not major offensives and are unlikely to capture large swathes of Ukrainian territory. However, they will keep the Ukrainians on the defensive in these areas, and possibly even draw the commitment of reserve forces being held back for exploitation of any breakthrough in the south. Finally, Gerasimov will be seeking the generate some minor success to retain the support of Putin.

Gerasimov’s Assessment: The First Seven Weeks of the Ukrainian Counter Offensive

While we are yet to see a large part of Ukraine’s combat power committed, Gerasimov has now had over seven weeks to observe and learn from the Ukrainian armed forces and the conduct of their attacks in the south and the east of Ukraine. While Gerasimov’s performance so far in this war may not have been terribly impressive, even he will have been able to take some lessons away from the past seven weeks and use these to adapt his dispositions and tactics in the coming months.

As such, what observations might Gerasimov have taken from the first weeks of Ukrainian offensive operations? This assumes of course that he has done some learning in between dealing with the Prigozhin mutiny, reinforcing his own position and conducting a mini-purge of Wagner-friendly Generals.

First, Gerasimov will have been reassured that the efforts to develop the extensive defensive positions in southern Ukraine are paying off. Having developed a doctrinal defensive scheme of maneuver, Gerasimov probably feels this has given him some breathing space to preserve his combat power in the south, while absorbing Ukrainian attacks and degrading Ukrainian combat power over the medium term.

The Ukrainian armed forces making progress in the south, but it has been as President Zelensky describes, slower than desired. There have been challenges with combined arms operations above company level and the quality of Ukrainian brigades engaged has been uneven. The observations of Franz-Stefan Gady and Michael Kofman, in the wake of their recent visit to Ukraine, are worth reading and reflecting upon.

That said, the slow Ukrainian progress is allowing the Russians time to attrit Ukrainian combat and support forces. The Ukrainian challenges in the south are also permitting Russia to run a global disinformation campaign with messaging about “Ukraine’s failed counteroffensive”, and “how supporting Ukraine is pointless.” This strategic messaging was reinforced by Putin himself at his 21 July Security Council meeting when he described how:

It is clear today that the Western curators of the Kiev regime are certainly disappointed with the results of the counteroffensive that the current Ukrainian authorities announced in previous months. There are no results, at least for now. The colossal resources that were pumped into the Kiev regime, the supply of Western weapons, such as tanks, artillery, armoured vehicles and missiles, and the deployment of thousands of foreign mercenaries and advisers, who were most actively used in attempts to break through the front of our army, are not helping.

Second, Gerasimov will be watching the correlation of forces in the south very carefully. While the Russian forces in the south are relatively fresh, the Ukrainians are extracting a significant toll on them.

One area of focus for the Ukrainians is degrading the Russian recon-strike complex, particularly artillery. Earlier in the war the Russians had a significant advantage in numbers of artillery systems, as well as the quantity of artillery ammunition. However, this advantage has been significantly reduced through provision of western towed, self-propelled and rocket artillery systems, as well as supply of Western precision munitions and Dual-Purpose Improved Conventional Munitions (DPICM)s. Gerasimov will be watching this battle of artillery systems in the coming weeks, and hoping there is not a tipping point where Ukraine gains an overall edge in this important battlefield capability.

For an indication of how this attrition of Russian artillery is going, see below the chart on Russian artillery losses since the beginning of June 2023.

Third, Gerasimov will be seeking ways to exacerbate and draw out the challenges that Ukrainian forces might experience in slowly fighting their way through the Russian southern defensive scheme. If he perceives he is being successful there, he may reinforce this ‘success’ through the construction of even more defences including minefields in the south, and other areas of occupied Ukraine.

Gerasimov probably assesses that short of a major NATO program to deploy large numbers of mechanised engineer vehicles - and possibly new ways to rapidly clear and penetrate minefields - Ukrainian progress in the coming weeks will remain challenging. That said, the UK, France, Germany and Italy alone possess over 250 armoured engineer vehicles, nearly 250 vehicle laid bridges and 500 armoured recovery vehicles (Source: The Military Balance, 2021). But even if this additional Western support was to eventuate, it would still require large-scale collective training to remedy some of the Brigade-level combined arms challenges that have been identified in southern Ukraine.

Fourth, Gerasimov will probably be thinking about options for Russian operations once the Ukrainian offensives have reached their culmination point. His assumption will be that Ukraine won’t make a major breakthrough in the south and the east. If that assumption does play out, Gerasimov may be considering offensive activity in other parts of the front line later in the year. And he will be talking with Shoigu and Putin about whether the offer of a ceasefire would be viable in the wake of a failed (in the Russian view) Ukrainian offensive.

That said, the ineffective offensives launched by Gerasimov this year consumed huge proportions of his forces’ ammunition and equipment in addition to the number of soldiers killed and wounded. This will constrain, but not entirely inhibit, Gerasimov’s ability to undertake any offensive activities now or later in 2023.

Finally, Gerasimov is probably still absorbed with the aftermath of the Prigozhin mutiny. Not only does he have to deal with his personal reputational impacts, but he is also probably leading the efforts to root out Wagner sympathizers. This will be having an impact on trust up and down the Russian chain of command in Ukraine.

Seven Weeks Down and a Long Way to Go

Gerasimov still has multiple challenges to deal with. Not only must he deal with higher level military strategy, and the coordination of Russian military operations, he must continue to provide the politico-military interface between the Russian military and President Putin.

A great survivor over the past decade of military reforms and defeats in Ukraine, General Gerasimov is likely to continue to execute his current defensive strategy in Ukraine. The Russian overall commander in Ukraine will be hoping that his plan will result in the Ukrainians culminating before they can break through the Russian defences in the south.

Both the Ukrainians and the Russians will have prepared themselves for a long campaign over the northern summer and autumn. The early 2023 strategic appreciations of the Ukrainian and Russian general staffs would have assumed that given the length of the front line, the size of respective forces in the field, and the determination of both sides to achieve their objectives, this was going to be a long campaign. So it has turned out.

Both sides, after their initial experiences in this Ukrainian 2023 counter offensive, appear to have taken stock, learned, adapted and put their heads down for the longhaul of military operations ahead.

Ukraine’s key is to continue to attrit Russian forces behind the defensive lines through HMARS, Storm Shadow, artillery. Logistics and ammo dumps have short lives behind the Surovikin line. Eventually the defensive wall will be hollowed out so long a Ukraine has ammunition. Then the breakthrough becomes easier. But the hollowing out of the defensive positions take time. In this sense this is likely the best outcome Gerasimov could hope for. And keep in mind Ukraine has retaken more territory in 7 weeks than Russia could capture in a year.

I strongly suspect that brigades are too large as presently organized to cope with pervasive surveillance and prompt fires. The much-reported issues with coordination could easily be misunderstanding the nature of what's happening - NATO training even of mid-level officers simply won't be able to reflect the new battlefield reality until curricula are dramatically updated.

A lot of NATO pros seem to be trying to scapegoat Ukraine for not proving that NATO doctrine and gear is magic. This is a different kind of battlefield than anyone has ever experienced before, and a lot of established old hands don't want to see a lifetime of investment in certain kinds of kit and gear prove to be a mistake.

Kind of wondering if NATO isn't in the position of the RAF back in the 1930s, flying a zoo of sometimes truly weird aircraft that didn't work well together. Then things got more standardized as lessons were learned in 1940-1941. A coherent theory developed.

My bet is that the future of warfare sees smaller teams overall. I wonder if the future base-level operational unit be a team of 6-10 armored vehicles and up to 100 personnel, basic task to slowly infiltrate forward across a 5km or even 10km front backed by massed precision fires...