Our view of any ongoing war is always incomplete.

This is because, like all wars, there are many things about it, even in this age of social media and greater battlefield transparency, that are yet to be revealed. Some of these unknown elements include secret intelligence activities, special operations missions undertaken by both sides, as well as the fears and motives of many key actors.

Our incomplete view is also due to the multiple levels of war from tactical to political. And it is because of the many humans, technological, conceptual, societal and organisational aspects that comprise a war. There are so many angles a particular conflict might be studied from.

This partial view is certainly true for the ongoing war in Ukraine. This makes predictions on the future trajectory of the war impossible.

But there are certain variables which are more likely than others to have a substantial impact on the course of the war in 2024. At this point, there are four key variables which are likely to shape this war in the coming year. My aim in this article is to explore these key variables.

But before I explore these variables, an update on Ukraine’s multiple campaigns is warranted.

The Ukrainian Campaigns of 2023

Over the last few months, I have explored the many different campaigns that are being executed by the Ukrainians. Their war cannot, and should not, be seen purely through the lens of combat in southern Ukraine. There is much, much more that is occurring and that can be observed and analysed to provide insights into the war’s progress.

Since the start of the Russian invasion, the Ukrainian Armed Forces have planned and executed military campaigns and operations within their borders and beyond. There are seven major Ukrainian campaigns currently being executed.

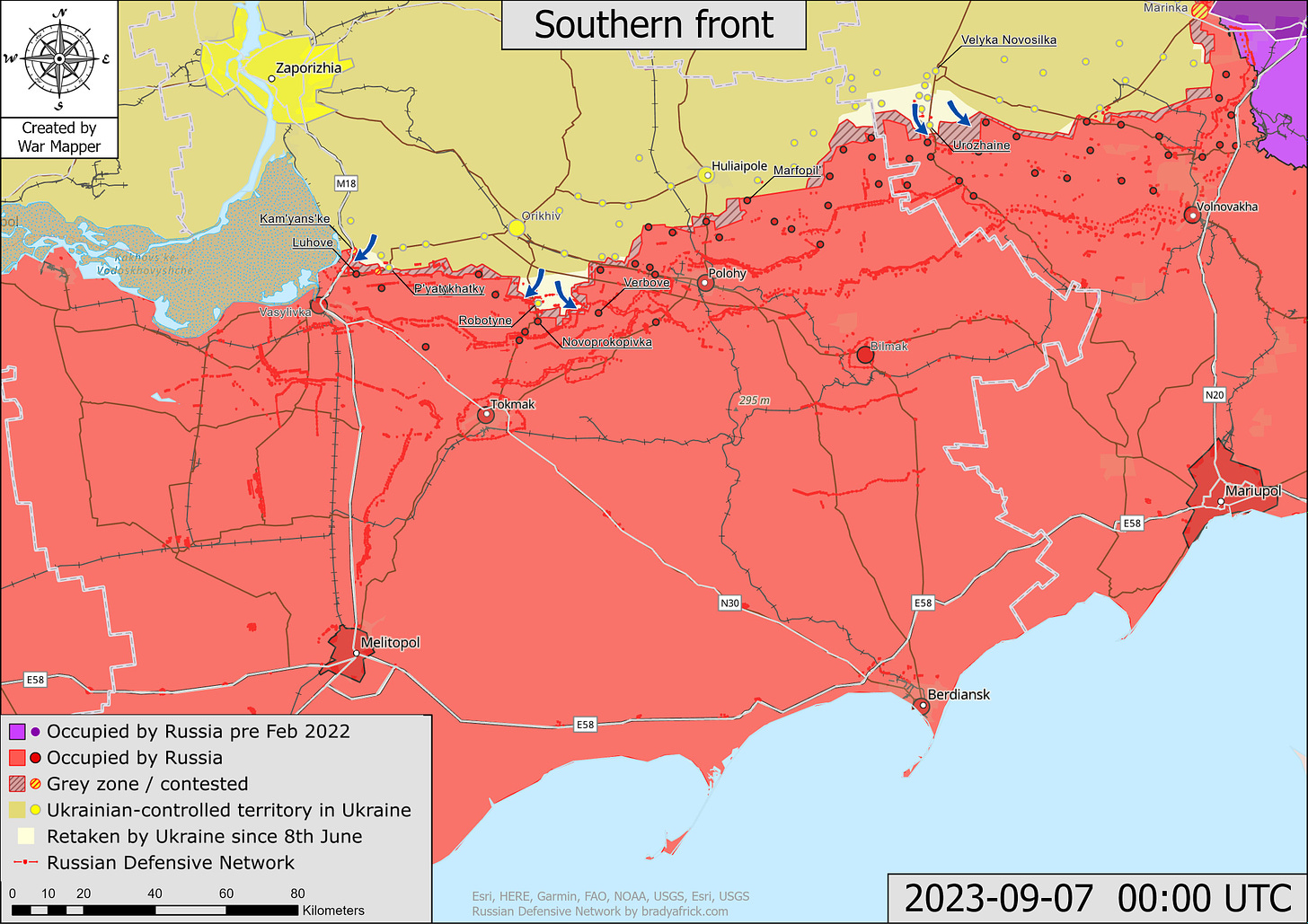

The Land Campaigns. The Ukrainian Armed Forces are executing three campaigns with their ground forces. In the south, Ukraine is advancing methodically on two major axes on the Donetsk and Zaporizhzhia fronts. They are chewing their way through a well-designed Russian defensive scheme of maneuver, particularly around Robotnye and Kamyanske, and gradually increasing the pressure on the Russians.

In the east, Ukraine is conducting an eastern offensive around Bakhmut and the vicinity of Avdiivka. Ukraine has made gains around Bakhmut over the past ten weeks. In the northeast, Ukraine is fighting a defensive campaign against the Russian offensive in Luhansk oblast. In particular, Russian forces have conducted offensive operations in the area of between the Oskil and Aydar rivers and have made minor advances. But Russia appears to be expending huge resources for small gains.

Operational Strike Campaign. Ukraine is also undertaking an operational strike campaign, which aims to corrode Russian fighting power in the south and east. This strike campaign is utilising long range missiles, including Storm Shadow and SCALP air-launched missiles, as well as maritime drones. Targets of this campaign include Russian logistic store locations, Crimean military targets, headquarters and important transportation nodes.

The Strategic Strike Campaign. Ukraine is accelerating its program of strategic strikes against Russia, and appears to have developed its own long range strike weapons that can strike within Russia. This includes multiple drone attacks on Moscow, including several in the past month. It also includes attacks on Russian airbases, the Belgorod incursions of this year, the recent attack on a Russian oil tanker, and multiple attacks on the Kerch Bridge. These strikes are more political than military. Their objective is to put pressure on Putin in front of the Russian people, and to answer for why he ‘can’t defend Russia’. They do however have secondary military outcomes in degrading strategic lift and strike assets.

As I have written elsewhere, we should expect that this strategic strike campaign will be an enduring one. Once land campaigns reduce tempo later this year with the coming of the muddy season, these strikes provide Ukraine with a method of continuing to hit Russia, and place political pressure on Putin. And, it increasingly has diplomatic support for such strikes. On 22 August, German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock supported Ukraine’s right to strike targets on Russian soil, saying that Kyiv acts within international law.

The Air, Missile and Drone Defensive Campaign. Ukraine is continuing its campaign to defend against Russian air, missile and drone attacks. This campaign, which began on the first evening of the war, has seen ongoing adaptation by the Ukrainian Armed Forces. They have absorbed multiple short, medium and long-range Western air defence systems, and integrated these with older Soviet-era systems to produce an effective air defence network. In the past day, Ukraine shot down 25 of 33 Shaded drones launched by Russia.

Strategic Influence Campaign. Providing support to all these campaigns is the ongoing Ukrainian strategic influence campaign. This has been a strategic undertaking since the beginning of the war. A recent component of this campaign has been the Ukrainian President’s lightening tour of Europe which has seen commitments for additional arms as well as provision of F-16 aircraft and training of their crews. However, with more positive western assessments of Ukrainian progress in the past couple of days, Ukrainian strategic influence activities are likely to leverage these assessments to gain more assistance and diplomatic support now and into 2024.

The Enabling Campaigns

In addition to these campaigns across multiple domains, there are a range of other less visible, but vital, enabling campaigns that are underway. These are important to understand because they are the firm foundation upon which combat capabilities rest.

A crucial campaign is training, which includes recruit training, specialist training and collective training, all of which are vital to sustaining frontline campaigns. It is likely that NATO is going to have to expand this effort in order to replace Ukraine’s combat losses, and to address the deficiencies in collective training that have become obvious during the summer offensives.

Another is the equipping and re-equipping campaigns for the Ukrainian armed forces. This includes the absorption of NATO equipment of many types, sourcing Soviet era equipment, munitions and efforts such as the Army of Drones initiatives.

Yet another important enabling campaign is cyber defence and ensuring the resilience of Ukrainian infrastructure against Russian cyber intrusion. These are critical for Ukraine’s overall war effort.

Key Variables for 2024

Ukraine’s ability to plan and execute similar campaigns in 2024 is well honed by contingent on several variables. While there is no lack of will on the Ukrainian part, the willingness and capacity of western support will influence the development and conduct of Ukraine’s 2024 campaigns. So too will the actions of Russia.

Variable 1. The first variable that will have an impact on the war in 2024 is the strategic dispositions of both sides once the muddy season, (bezdorizhzhya in Ukrainian) hits, which is around November. Ground operations, particularly cross-country mobility, after this will become increasingly difficult. At the same time, both sides will be increasingly restricted to formed and sealed roads, which will make their logistic support simpler to find and target.

Consequently, the Ukrainians will want to gain as much ground as they can before this time. For the Ukrainians, they will probably want to have – at a minimum - gained fire control on one axis of advance in the south of Ukraine all the way to the coast. They don’t necessarily have to occupy this territory (yet) but holding the entire area at risk will make Russian resupply very difficult. Especially when it will be restricted to known routes during the muddy season.

In the east Ukraine will want to ensure it also has fire control over Bakhmut. The objective will be to ensure Russia keeps feeding in troops that Ukraine can target. It does not (yet) need to take Bakhmut, but it is a good opportunity to destroy better quality Russian units and draw Russian reserves from the south.

From Russia’s perspective, they will want to avoid Ukraine gaining fire control over their southern Ukraine routes and make gains in their north-eastern offensive. These have a military impact.

For both sides, their dispositions in November will have a political impact. It will have an impact on the morale of troops on both sides and will affect discussions in Western capitals about support for Ukraine in 2024.

Variable 2. The second strategic variable is the level of remaining munitions holdings as well as spare barrels, and counter-battery radars on both sides. The consumption of munitions in Ukraine has been significant and is the first to challenge post-Cold War defence industrial and strategic logistic models.

But even with the growing use of precision munitions by both sides, large amounts of ammunition will still be required over Winter. Larger amounts will need to be stockpiled to prepare for the inevitable 2024 offensives.

There is only so much that can be drawn from existing Western stockpiles, whether it is munitions or equipment. In the short term, the provision of DPICM munitions to Ukraine by the U.S. is helping bridge a gap in production capacity. But the longer-term solution is expansion of production. The Ukrainians are doing some of this themselves, but U.S. and European capacity will also be crucial.

The U.S. has indicated that it will do so but this is still some time from having an impact. The U.S. began increasing production last year, and has increased monthly production from 14,000 155mm rounds to 24,000 now. This still doesn’t meet monthly Ukrainian needs. Europe has also made some announcements about expanding production. And while there has been some criticism that this is more talk than action, even if production began soon European increases probably won’t have an impact until 2025.

Russia will also become reliant on external support as it ramps up its own production capacity. One external actor that might be important to Russia in 2024 in this regard is North Korea. While I would not want to be using their low-quality ammunition, the Russian rationale will be ‘better to have low quality ammo than no ammo”. This could impact on the battlefield in 2024.

But munitions are not the only consumable that could have an impact on the war in 2024 if bottlenecks arise. Another key battlefield item is drones. There have been shortfalls in these at times. What if exploding demand in Ukraine, and beyond, results in supply bottlenecks?

Variable 3. The next variable is the ability of Ukraine and Russia to mobilise, train and deploy more troops. Ukraine mobilised its forces early and has been constantly training regular and territorial forces for defensive and offensive operations. At the same time, it probably has expended huge training resources in building a maintenance workforce for the menagerie of different NATO platforms in now possesses.

Collective training quality will be a key part of this variable. As we have seen in the ongoing Ukrainian offensives, there has been a variety in the quality of brigades. This is not to be critical; it is difficult to train individuals and then work them up through the various levels of collective training needed.

NATO needs to step up collective training for Ukrainian formations over winter and into 2024. It also needs to look at doctrine for combined arms combat under modern conditions. Whether it can do this will have an effect on military operations next year.

The Russians, after a ‘partial mobilisation’ in September 2022, and ongoing recruiting of about 20-30,000 per month, may still need another mobilisation late this year to rebuild units destroyed or severely weakened during the summer Ukrainian offensives. However, previous speculation on this topic has proved unfounded.

Whether through ongoing recruiting or another mobilisation, the influx of tens of thousands of new Russian troops in 2024 would present a challenge for Ukrainian strategy moving into 2024. The ability for either side to most effectively mobilise their population, and then to suitably equip and train them, and deploy them to the right place at the right time, is a key variable in this war for 2024.

Variable 4. A final variable for the war in 2024 is the willingness of external supporters to continue providing military, diplomatic, economic and humanitarian assistance. The West has often taken a stepped, too-slow approach to providing sophisticated weapons, providing tanks, fighter aircraft and long-range missiles. And there are still some in the U.S. and Europe who see the provision of more advanced weapons as escalatory. But Ukraine can’t win this war by defensive operations only.

As Ukraine’s recent strategic strike campaign has shown, long range strike can affect the war without major Russian escalations. This should permit Western politicians to double down on their support to move from a defensive approach to supporting a decisive Ukrainian victory.

An interesting aspect of this variable is the willingness of China to remain ‘neutral’ in this war. China still imports record amounts of Russian coal, LNG and oil, providing revenue for Putin’s regime. And it still exports to Russia dual use items.

A final consideration is the strategic leadership of Putin and Biden – and their ability to nurture and sustain the will of their people.

Putin’s direction launched this war. He is playing for time, hoping that the west gradually tires of the war in 2024. This was also his theory of victory going into 2023, and it has not yet worked out for him. Will 2024 be different?

Biden’s leadership has been vital in hardening western resolve and coordinating a steady flow of aid to Ukraine. But the 2024 US election season will result in closer scrutiny of aid to Ukraine. Biden may also come under greater pressure to explore peaceful resolutions to the war.

The capacity for Biden and Zelensky to keep Europe and America unified in its support for the Ukrainian war effort – or to even increase support to ensure a Ukrainian victory - will be a key variable in the year ahead.

Nothing is Certain about 2024

Nothing in war is certain. And 2024 will present a range of strategic activities external to Ukraine and Russia that could have significant effects on the war efforts of the two nations.

The U.S. presidential election year is certain to be a difficult one, and there is a strand of Republican thinking that wants to either reduce support because of ideological reasons or because of a desire to focus on China. And as a Pew Research centre poll showed earlier this year, there has been a decline in the number of Americans who view the war in Ukraine as a major threat to U.S. interests.

But elections in places such as Taiwan, India, Belarus, Georgia, South Korea and Indonesia (as well as Russia) could all change the strategic environment in ways we have not anticipated.

At the same time, strategic patience is a valuable and often limited commodity. An August 2023 poll by CNN showed 51% of Americans believed the U.S. had done enough to help Ukraine. Given this war will continue into 2024, sustained efforts will be required by western governments to keep their citizens informed about the reasons for supporting Ukraine.

The exploration of different variables that will have an impact on the trajectory of the war is useful. In doing so, we can ascertain Russian weaknesses that might be exploited. We might also ensure that the right kinds and quantities of support are provided at the right time to Ukraine for 2024 (and beyond).

Excellent. While I completely agree with your “four variables” I would add a fifth, which could have a significant impact as early as 2024. Kim Jung En is craftily using his leverage to pry nuclear and missiles technologies out of Russia that North Korea is having difficulty developing. Nuclear propulsion technology and missile warhead technology are two areas he has been asking for. However, the fifth variable is probably the sticking point in all these negotiations - money. Russia’s income from its only real exports - oil and gas - has dropped like a rock and its “alternate” customers (China and India) are paying in their local currencies - not dollars. Russia is running through its sovereign wealth fund like water even using their (very questionable) figures. How long can this continue? Cuba, Venezuela, North Korea and Iran have proven resilient outside the global economy. Can Russia? It remains to be seen. While Russia may be able to trade its technology and “high tech” weapons to North Korea and Iran for shells and drones, will that be enough? Putin is afraid of his population. Defeat on the battlefield, further mobilization and a deteriorating economy are going to make his life very difficult.

Mick, another great piece on strategies and preparation going forward. It takes great humility to recognize that as much as we can observe and know from our experience predicting the future direction of a war is folly for all the reasons you stated. What is role of surprise and contingency planning going forward and what does that look like? Though never a fan of Rumsfeld, his characterization of “known unknowns and unknown unknowns” does ring true. What are the possible “known unknowns” around which contingency planning can be done? How can Ukraine or Russia prepare for realizations of events that were not foreseen as possible? On this last point I would think Ukraine is better equipped with more decentralized and flexible decision making than Russia.