Has Russia Blown its 2024 Opportunity in Ukraine?

Russia may never get an another opportunity like the past six months. An updated assessment of Russia’s 2024 offensives.

Back in May, I explored the potential Russian objectives for its military operations in 2024, and how it was progressing towards those objectives.

Russia has built strategic momentum with its ground and aerial assaults on Ukraine over the past six months. Most analysts of the war agree that Russia still has the initiative in this war. But what does that really mean for Russia’s prospects in the war, and the possibility of it achieving its strategic objective of subjugating Ukraine and ensuring Ukraine cannot provide an alternative model of governance visible to the politically repressed Russian people?

To assess how Russia’s 2024 campaigns in Ukraine is going, and whether it has maximised its opportunities this year, it is necessary to briefly explore what Russia set out to achieve in Ukraine this year. Back in early April, I explored how the Russians might view success in 2024. You can read that article here.

However, to summarise, what does Putin want in 2024?

Putin’s 2024 Objectives for Ukraine

Putin's 2024 objectives for his war against Ukraine are hardly a mystery. Described in his speeches on February 21 and 24, 2022, in the many of his speeches since that time including his March 2024 post-election victory speech, Putin aims to do everything possible to ensure that the world understands that Ukraine is not a sovereign nation.

It goes without saying that Putin will want to keep western politicians cowed an in a state of ‘escalation terror’ by regular reference to nuclear weapons.

Additionally, Putin, who wants to reassert what he describes as Russian civilisation in his part of the world. He has also has consistently portrayed Russia as the victim of a NATO plot and Ukrainian "Nazis". This is a narrative that he continues to employ. As Illia Ponomarenko describes it in his excellent new book, I Will Show You How It Was, these Putin speeches and accompanying misinformation has become a “hateful propagandistic stink wafting from the east”.

An Updated Assessment of Russia’s 2024 Offensives

Russia continues its ground offensives along multiple axes of advance: Bakhmut; Avdiivka; Kupyansk; Novopavlivka; Robotyne; Belgorod-Kharkiv; and Kherson. It is also waging a nightly air, missile and drone campaign against Ukrainian infrastructure, defence industry and civilian targets, in addition to its tactical ground attack campaign utilising long-range glide bombs. All of this is reinforced with Russia’s strategic misinformation and diplomatic campaigns, as well as its European sabotage operations.

So, Russia is undertaking many operations and expending a lot of resources. What is it getting in return for its investments in people, treasure, information and time?

To assess the Russian return on investment, I will again employ the measures of success that I proposed for Russia’s Ukraine campaign back in April, and which I also used in my May assessment of Russian operations. Against each, I again provide an assessment of Russian progress (or otherwise).

Measure 1: Russia is able to neutralise Ukrainian strategic strike activities. (Impact desired by Russia: Strategic and operational levels, some political impact). One of the key Ukrainian strategic capabilities which is employed to hurt Russia politically and to hinder its war-making capacity is its very capable strategic strike complexes. As I have described previously, there are three distinct Ukrainian strike complexes that the Russians must degrade or neutralise; the Navy’s maritime strike complex in the Black Sea; the Intelligence communities strike complex; and the Ukrainian Armed Forces broader strike complex.

So far, Russia has made little headway in reducing Ukraine’s capacity to attack an array of strategic targets including oil refining and export facilities, strategic airbases, as well as significant radar and air defence installations. If anything, Ukraine’s strikes have stepped up a notch since they were provided with additional ATACMs missiles by the US. While Russia has increased the amount EW and air defences around many sites within Russia, there are probably too many potential targets for it to fully cover. And, the reality is that U.S. restrictions on the employment of ATACMS in Russia is probably more of a hinderance to the Ukrainians than Russian defences.

As such, the best assessment that might be made against this measure of success for Russia is that they are failing, with few indications that Russia will improve their ability to degrade or neutralise Ukrainian strategic strike capabilities.

Measure 2: Russia is able to destroy or degrade Ukrainian tactical and operational reserves, C2 and logistics over the course of 2024 (Impact desired by Russia: tactical, operational and strategic impacts – medium term). The Russians aim to limit Ukraine’s capability to respond to Russian ground and air attacks throughout 2024. Therefore, finding and neutralising mobile Ukrainian ground force reserves is an important Russian objective. So far, this has only been partially achieved. Russian assaults across the east have steadily attritted Ukrainian front-line brigades, which remain in need of reinforcements.

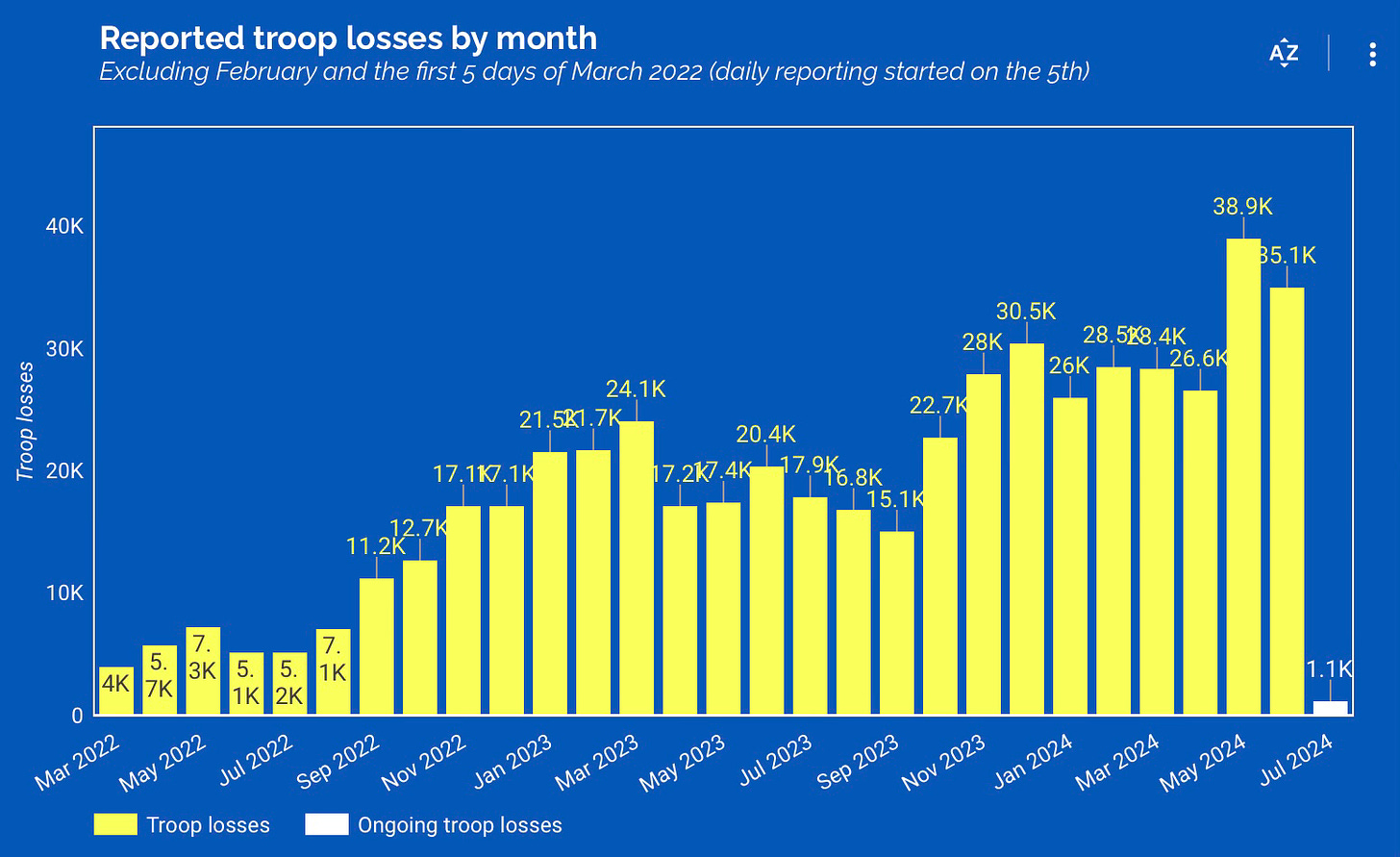

However, Ukraine has probably been attriting Russian forces more. A recent statement by President Zelensky noted that Ukraine is imposing a 6:1 loss ratio on Russian military personnel in Ukraine. Other sources have noted that Russia over the past month is on average losing over 1000 troops killed and wounded per day. The chart below shows aggregated losses per month, with a significant increase since the Russian offensive began. Even if Russian is able to recruit up to 30,000 troops per month, as some reports suggest, this number is only enough to reinforce and cover losses. It is not enough to build up additional strength for any major Russian offensive.

While the exact figures are very difficult to verify, it is logical that a force on the attack will sustain more casualties than that on the defence. This is even more likely when the demand for reinforcements means that replacement troops are receiving steadily less training and therefore have lower survival rates once they reach the battlefield. No country can continue indefinitely to sustain such casualties. This is especially the case if they have minimal gains to show for such massive losses.

Therefore, the assessment must be that Russia is experiencing limited success in the attrition of Ukrainian forces in 2024, particularly as Ukrainian recruiting and new U.S. / European military assistance as well as Russian battlefield casualties are steadily eroding the Russians massive advantages in manpower and firepower that it had for the first half of 2024.

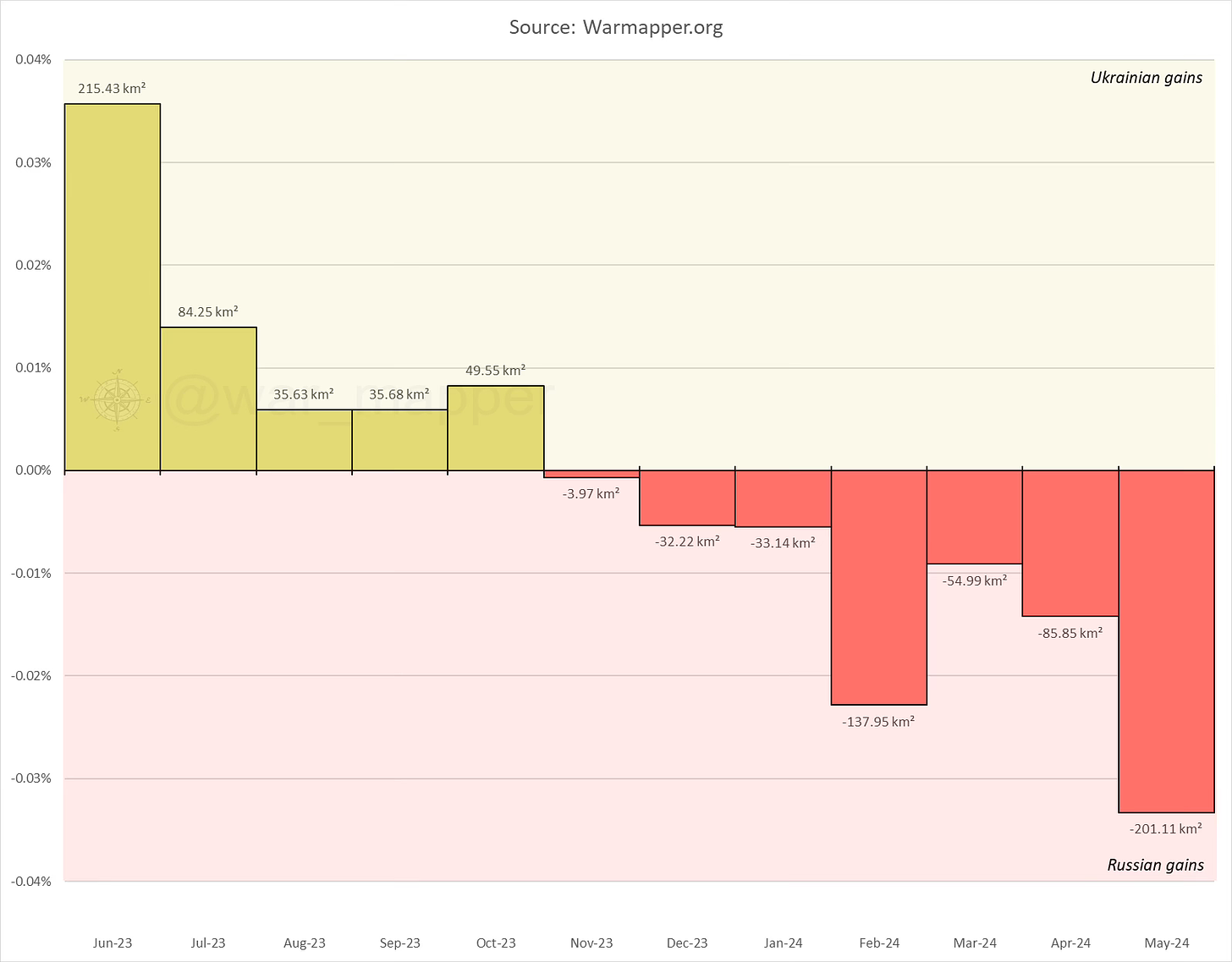

Measure 3: Russia seizes additional Ukrainian territory (Impact desired by Russia: tactical and operational, but with significant political ramifications). Underpinned by tactical and operational battlefield successes, seizing additional large parts of Ukrainian territory is an important measure of success for Russian in 2024. Over the past several months, Russia has been able to achieve some advances in the east and northeast, and it has captured additional Ukrainian territory. The total gains since the beginning of 2024 however add up to a total of approximately 513 square kilometres of Ukrainian territory seized. (Ukraine overall is 600,000 square kilometres).

This is a very poor return for the massive numbers of troops lost (around 183 thousand according to Ukrainian sources) to achieve such paltry gains. It represents a loss of over 360 Russian troops for each square kilometre gained.

Perhaps the most important gains in the east have been the capture of Avdiivka in February 2024, the creation of a significant salient in the Ocheretyne area from which it continues to drive slowly west, as well as its capture of territory in the Kharkiv region more recently. However, the Kharkiv offensive has probably culminated. Russia will seek to use captured ground as a buffer zone as Putin recently described, it could possibly use it for future thrusts towards Kharkiv to hold it at risk with artillery. This is unlikely in the short term, however.

As such, Russia could be assessed as having achieved some success on multiple axes of advance since January 2024. However, the gains that a more coordinated, better trained and better led Russian Army might have achieved against a smaller, less well-equipped defender have not materialised.

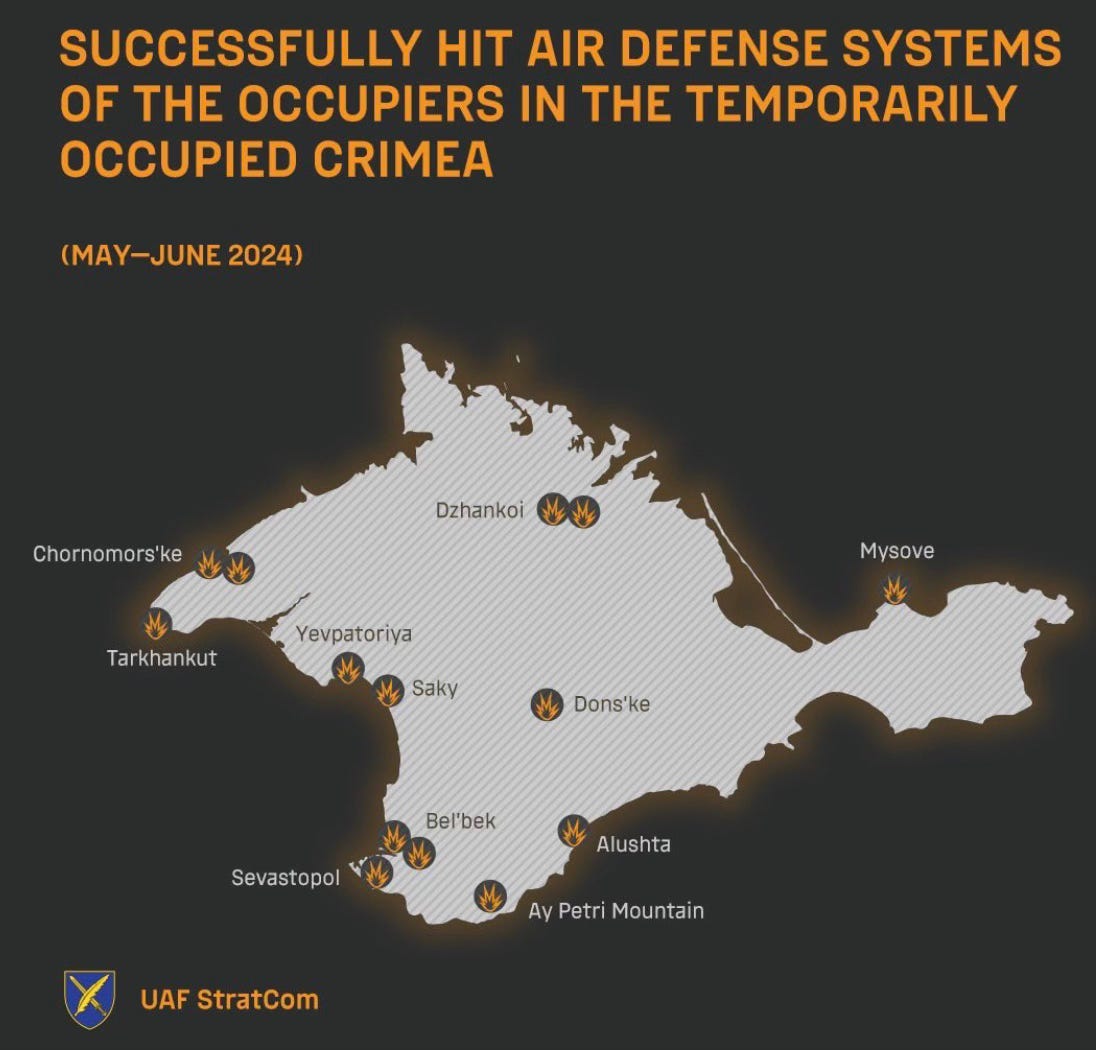

Measure 4: Russia decreases the number and impact of Ukrainian attacks against Crimea (Impact desired by Russia: Operational, strategic and political – medium term). Making Crimea untenable for Russian military forces is a Ukrainian objective and President Zelensky has been clear that this is one of the Ukrainian war termination conditions. Multiple strikes against Russian airfields, logistics sites and air defence establishments, as well as the harassment of large portions of the Black Sea Fleet away from its Sevastopol operating base, indicate that Ukraine’s campaign is going well. Ukraine has stepped up Crimea attacks with the recent addition of U.S. ATACMs missiles. Given there are no restrictions on the use of the missiles on Ukrainian territory, Crimea is likely to continue being hit by these missiles.

Ukraine has successfully conducted strikes against Crimea every month this year, except April, destroying headquarters, air defence systems and aircraft on the ground. Ultimately, Ukraine will want to destroy the Kerch Bridge as an important military and political target.

Russia continues to have limited success in reducing Ukrainian attacks against Crimea. As such, the assessment of this measure of success for Russia is that it continues to fail miserably with no indications that it can turn around this situation.

Measure 5: Russia captures or destroys Ukrainian forces (Impact desired by Russia: tactical and operational, but with political and strategic ramifications). The Russians want to be beat Ukraine on the battlefield and understand that Ukraine can less afford casualties than Russia can. Successful Russian offensive operations will seek to continue reducing the quantity of Ukrainian deployed ground forces, particularly before the impacts of Ukrainian mobilisation are realised. However, as discussed above, this will be very difficult to achieve with a 6:1 loss ratio in favour of the Ukrainians. And with Ukraine beginning to recruit and conscript more into its ranks after the recent mobilization debate concluded, it is difficult to see the Russian performance improving on this front.

The assessment of this measure of success for Russia is that it has not yet achieved this objective despite its attrition of the Ukrainian Armed Forces overall. Choosing to fight how it is, Russia is probably imposing more attrition on itself than the attrition it is imposing on the Ukrainians.

Measure 6: Russian misinformation and other influence activities degrade the cohesion of Ukrainian society (Impact desired by Russia: political and strategic). Russia is currently undertaking a broad array of measures that are designed to fracture Ukrainian society and to undermine trust in their government and military. It will continue to amplify messaging about corruption and to decrease the willingness of Ukrainians to serve in the military.

Russian misinformation, propaganda and other malign information activities are being undertaken in Ukraine. A recent report described how Russia is pouring up to 1 Billion dollars into a misinformation campaign called “Maidan-3” that was launched by Russia last November. The Ukrainian security services have arrested multiple people in the past year, including two colonels accused of plotting to assassinate President Zelensky and other accused of spying and spreading misinformation. The Russian attacks on power infrastructure, which has been one of the few areas where the Russians have seen success in the past six months, has probably had a larger impact on Ukrainian society than its other influence activities.

The assessment of this measure of success for Russia is that it has a very robust misinformation campaign running in Ukraine and it has spread a multitude of rumours and stories about corruption, mistreatment of military recruits and has distributed a range of misinformation products. It is yet to achieve any significant fracturing of Ukrainian society or major schisms between citizens and their government.

Measure 7: External observers of the war, whether they support Ukraine or not, believe Russia’s 2024 offensives have been a success (Impact desired by Russia: political and strategic). Not only must Russia achieve tactical and operational success in its operations, foreign leaders and citizens in the West and beyond, will need to think Russia has succeeded.

The continuous Russian misinformation campaign is key to how they tell their version of the war’s rationale and progress. The long-delayed U.S. assistance package to Ukraine was an opportunity that Russian misinformation purveyors but that opportunity has passed. The Russian themes of ‘inevitable Russian victory in the war’, that it is ‘a war forced on Russia by NATO’, and that it is ‘an eastern European issue only’ appear to have resonated with some audiences not only in the global south but in western nations such as America and Australia. And while a Trump victory in November appears to be something that Russian misinformation operations are likely to support, it remains unclear whether this would actually be a positive for Russia.

It is also worth noting that recent polls in the U.S., Britain, and Australia have shown a continuing high level of support among citizens for supporting Ukraine in its fight against Russia. For example, the recent Lowy poll in Australia finds that:

Australian public support for assisting Ukraine remains high. The vast majority of Australians (86%) continue to support ‘keeping strict sanctions on Russia’, steady from 2023. Eight in ten (80%) support ‘admitting Ukrainian refugees into Australia’, down four points from last year. Three-quarters (74%) support ‘providing military aid to Ukraine’, steady on last year.

The assessment of this measure of success for Russia is that it has experienced success in 2024, and throughout the war, in its strategic influence efforts. It has run a sophisticated international campaign that cuts through in many audiences. Despite this, it is yet to result in significant drop offs in military or economic assistance for Ukraine, or for significant pressure from major western nations for Ukraine to negotiate for an end to the war with Russia.

Assessment

The Russian military had a significant opportunity at the end of 2023. The Ukrainian military had culminated in its counter offensive in the south, although there remained very capable Ukrainian ground forces deployed in the east. The Ukrainians had probably used a large amount of their ammunition and air defence stocks, and without a confirmed replenishment from the Americans, faced months of drastic shortages. Concurrently, the Ukrainians continued to debate their approach to mobilization as shortages in manpower, especially on the frontline, became acute. Many brigades in the first half of 2024 were sitting at about 50 percent of their authorised personnel establishment. Politically, the U.S. congressional debate about assistance to Ukraine led to a fracturing of support in the U.S. along party lines.

And yet, the Russians over the last six months have generally failed to capitalise on this convergence of opportunities. They have managed to eke out advances in the tens of kilometres in some areas, with the overall territory seized adding up to just over 500 square kilometres in the past six months. This is an area that is a bit bigger than the Isle of Wight in the UK, about two-thirds the size of New York city, slightly smaller than the Isle of Man and about 3% the size of where I live in Brisbane, Australia. It is hard to call this anything remotely like a success when it required over 180 thousand casualties to achieve.

And in throwing away such enormous quantities of troops in many small actions across the front line, Russia is less able to build a better quality, large force that might be able to undertake larger scale offensive operations. As Dara Massicot has written:

Because Gerasimov is still commander. Since spring 2023 he’s shown no inclination to preserve/consolidate the larger force, and by always attacking, burns through men+equipment in ways calibrated to be sustainable in the short term but create long term weaknesses.

The Russians have squandered a strategic opportunity to make significant gains since January 2024. This was probably Russia’s last, best opportunity to make significant gains on the battlefield which it could then turn into significantly increased political and diplomatic pressure on Ukraine for peace negotiations. That Russia, with its significant advantages in manpower, firepower, electronic warfare, finances and defence industrial production was not able to realise the potential of these advantages is an indication of shortfalls in its strategy, strategic leadership as well as the overall quality of its military. It again provides evidence of how corrupted the 2012-2022 strategic transformation activities, led by Shoigu and Gerasimov, were.

Russia has however demonstrated an ability to learn and improve its performance since the beginning of the war. It has evolved its higher command and control arrangements and has significantly improved their industrial support for the war. The Russians have also experimented with force structure changes and tactics. The recent development of turtle tanks, the employment of small-scale infiltration tactics, using different types of drones and missiles in their aerial attacks, and the conduct of multiple attacks simultaneously across the front are evidence of this willingness to experiment on the battlefield.

And, as I have written previously, Russia has probably developed a better approach to strategic adaptation than the Ukrainians have. This is allowing them to out-produce the Ukrainians in many types of munitions and to continuously recruit new meat for their high-cost military assaults.

But these are only providing marginal improvements in the tactical and operational effectiveness of the Russian military. And, as I have highlighted elsewhere in this assessment, these marginal improvements are disproportionate to the massive losses in manpower and equipment they have expended to achieve such small gains.

Unless a Trump victory in November results in a drastic reduction in U.S. support for Ukraine, Russia is unlikely to be gifted another chance like the one it has had in the past six months to make progress in the war. European defence industrial capacity is increasing, and its political resolution to resist Russia is strengthening. Ukrainian defence production is increasing. But then, Russian defence production has also exceeded the expectations of most western analysts. Whether this can be continued indefinitely is another question.

Ultimately, the past six months offer another case study of a military institution that has failed to effectively change its doctrine, training, structure and equipment during wartime in a way that increases its chances of tactical, operational and strategic success. The Russian gains hardly justify the burning through men and materiel that has taken place since January 2024.

The sources of their failure to capitalise on their strategic opportunity in 2024 are many. Russia has yet to develop a new offensive doctrine for land operations in modern conditions. It has not been able to balance quantity and quality across the force, generally leaning on mass for its attacks. Its military leadership is clearly not capable enough to build and implement the right military strategy for such an intellectually demanding war. And Russia’s style of fighting in 2024, and how poorly it treats Ukrainian civilians and soldiers, has meant that Ukrainian resolve is sustained. In due course, the Russian 2024 offensives will be added to the failed campaign for Kyiv in 2022, and the failed 2023 Ukrainian counter offensive, as examples for military analysts and scholars to study well into the future.

Russia may still have a couple of months where they can conduct more offensive activities against Ukraine before they culminate. But, given Russian losses so far, the lack of any new, wide-ranging offensive doctrine, and that Ukraine’s strategic prospects are improving with respect to manpower, air defence and munitions, Russia appears to have blown what might have been its last chance to strike a decisive blow against Ukraine in this war.

The question now is whether Ukraine, which wants to liberate more of its territory occupied by Russia, can build all the different physical, moral and intellectual elements of offensive combat power to do better than Russia has either later this year or in 2025?

Excellent piece. The only thing I would add is the economic variable. By many accounts Putin is not only degrading his manpower reserves with little gain, he is blowing thru his economic reserves as well. While Russia is reporting 3.5% GDP growth, when you look at the numbers, all the growth is from the government spending on the war and they are spending their reserves at a prodigious rate to do so with no way to replenish them. There is a much better chance that this war will end on the economic front rather than the battlefield.

F-ing excellent. Thank you.